Ohio history

Steve Stolte was a civil engineering student at Ohio State University when the Silver Bridge, which connected Gallipolis to Point Pleasant, West Virgina, on busy U.S. Route 35, collapsed into the Ohio River.

After the collapse, Ohio began to require that all bridges in the state be inspected once each year. Seeing an opportunity to both make some money and potentially save some lives, Stolte and some of his college friends started up a new business.

They attended classes during the week, but on weekends they traveled into rural counties throughout the state to perform those mandated bridge inspections.

“We learned quickly to drive across each bridge prior to doing our inspection, because we often didn’t want to drive across after seeing the condition they were in,” he says.

When Francis de Sales Brunner, a Catholic missionary priest from Switzerland, first came to what is now Mercer County in the mid-1840s, one of the substantial number of religious artifacts he brought with him was a depiction of a miracle in which the Virgin Mary is said to

His original collection, expanded through acquisitions and donations over the years, has grown into one of the largest collections of holy relics in the country, and today, the Maria Stein Shrine of the Holy Relics draws visitors from around the world to pray and reflect among more than 1,200 documented pieces displayed in a series of three hand-carved wooden altars and assorted glass cases.

On November 14, 1935, nearly 500 people, including local, state, and national dignitaries, gathered in the shadow of the municipal light plant on the west bank of the Great Miami River in Piqua to watch as a wooden pole was set into the ground.

Joslin grew up in Sidney, and moved to Wyoming after high school to be a sheep rancher. After six years, he returned to Ohio to farm, and in 1917, he helped found the Shelby County Farm Bureau, laying the foundation for cooperative action. Reserved but determined, Joslin became known for his ability to earn trust and get results — he was well known for his mantra, “Let’s get it done” — and in 1935 he was the county farm bureau’s president.

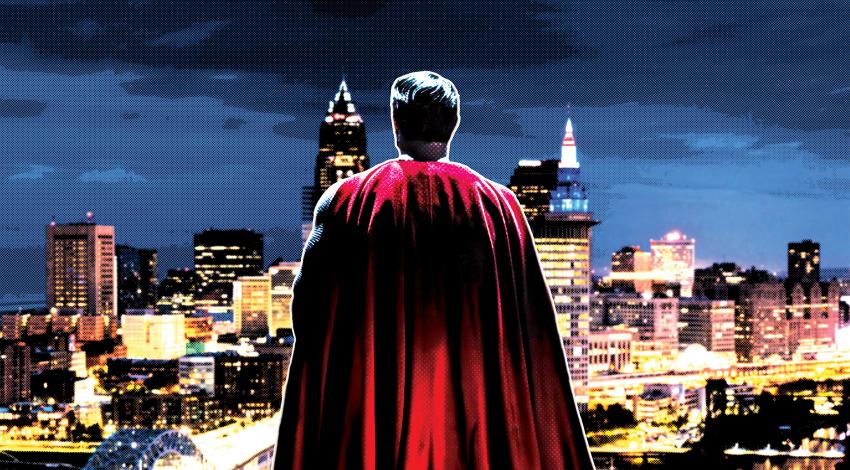

“Up, up, and away!” Before Superman became a global icon, he was a glimmer of hope imagined in a Glenville bedroom.

“Superman is one of Cleveland’s greatest exports,” says Valentino Zullo, assistant professor of English at Ursuline College and co-director of the Rustbelt Humanities Lab. “We’re not exporting steel; we’re exporting culture. The superhero genre was created here.”

“No colony in America was ever settled under such favorable auspices as that which has just commenced at the Muskingum.

When Ohio gained statehood in 1803, leadership recognized the potential of the Muskingum to facilitate the opening of Ohio and the entire Midwest for increased trade and development. As a result, in 1837, the legislature began funding construction of a series of 11 locks and dams on the river, spending $1.6 million over the next four years (roughly the equivalent of $1.4 billion today) for what was one of the most extensive — and expensive — public works projects of its kind in America at the time.

In 1957, humorist James Thurber wrote to Columbus Dispatch writer and artist Bill Arter to discuss the future of the house where Thurber had been born.

Not a bad local legacy for a humor writer and cartoonist who frequently made his hometown and its inhabitants the butt of his jokes. In stories like “The Day the Dam Broke” and “University Days,” the good citizens of Columbus and its land grant college, Ohio State University, were often portrayed as naïve or foolish at best, bumpkins at worst. But overall, his portrayal was fond, says Leah Wharton, operations director at Thurber House.

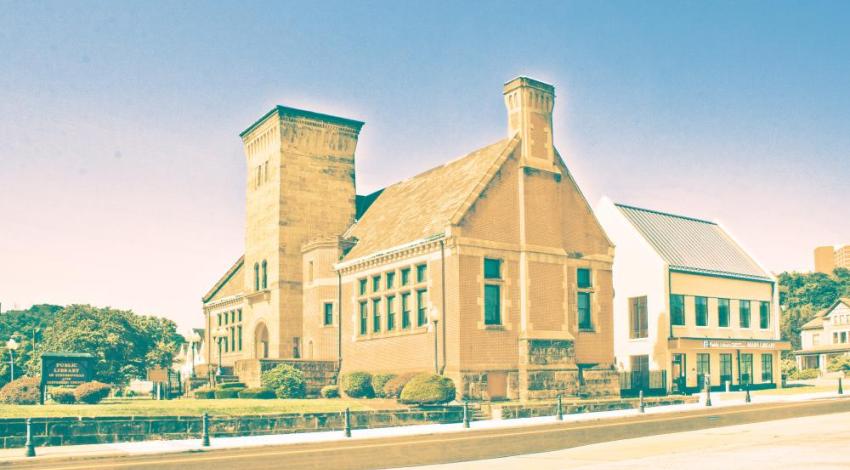

Among the many documents stored in the Archives Research Center at the Sandusky Library is a copy of a letter dated Oct. 7, 1899, and signed by Andrew Carnegie.

Carnegie, in fact, eventually became the wealthiest person in the world in his time, thanks to early successful investments in the railroad industry and building what eventually became U.S. Steel. And he followed through on his musing. Carnegie — and later his philanthropic foundation, the Carnegie Corporation of New York — gave away most of his fortune in his later years, spending much of it on free-to-the-people libraries.

Of Ohio’s 88 counties, eight are named for Indian tribes: Delaware, Erie, Huron, Miami, Ottawa, Seneca, Tuscarawas, and Wyandot.

In development since 2019, Ohio’s newest state park is located along U.S. Route 68 just north of Xenia, where “Old Chillicothe” — a historic Shawnee village — once stood. As Gov. Mike DeWine said at its June 2024 grand opening, “The land had a story that needed to be told.”

Constantine Rafinesque-Schmaltz is the scientist you did not know that you knew. His walkabouts through Ohio impressed upon him a desire to discover more about plants and fishes and a prehistoric culture that predated him by millennia.

The family moved to Italy to escape the terrors of the French Revolution. It was there that a self-educated Constantine came of age and took an ardent interest in natural history and languages, which would come to have its consequences in the names of organisms — through the eastern U.S., in Ohio, and even into the American Southwest.