Constantine Rafinesque-Schmaltz is the scientist you did not know that you knew. His walkabouts through Ohio impressed upon him a desire to discover more about plants and fishes and a prehistoric culture that predated him by millennia.

This self-educated polyglot and polymath possessed a brilliant and inquisitive mind, an unceasing curiosity — and an eccentric and prickly personality that made him easy to dislike.

But let’s go back to the beginning. He was born in 1783 in Turkey and spent his youth in France. His father was French, and a successful international merchant. His mother was born in Germany, and her son carried her name until adulthood. His father died of yellow fever when Rafinesque was but 10 years old.

Constantine Rafinesque-Schmaltz published 900 scientific papers and several books, and named 6,700 plants, several species of turtles and mammals, including deer and coyote, and 26 fishes native to Ohio.

The family moved to Italy to escape the terrors of the French Revolution. It was there that a self-educated Constantine came of age and took an ardent interest in natural history and languages, which would come to have its consequences in the names of organisms — through the eastern U.S., in Ohio, and even into the American Southwest.

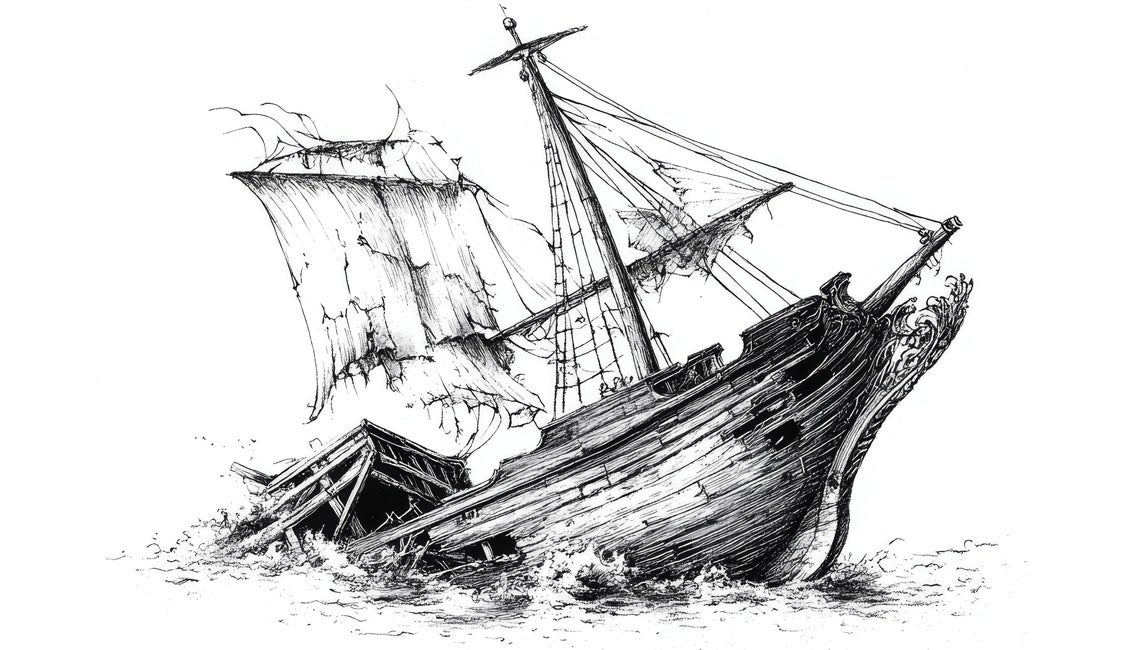

Rafinesque lived through a number of tragic incidents over many of his 56 years. While still a precocious young man, he collected and described for science (that is, to give an organism its first formal scientific name) new plants and fishes from Sicily. Striking out on his own, the young scientist traveled to the United States anticipating museum work. Then, tragedy hit in 1815: He lost all of his belongings, papers, books, and his collected plant specimens along the Atlantic Coast in a shipwreck — and he nearly lost his life.

He landed on America’s shores in Connecticut with nothing but the drenched clothes that he was wearing. He eventually established himself as a serious botanist in New York.

The man collected and described plants with great frequency and intensity. He habitually wore a long coat with many pockets to stash plant specimens to preserve and describe.

He had interests beyond plants. In 1818, Rafinesque walked the length of the Ohio River from Pittsburgh to southern Illinois, collecting plants and fossils and catching and drawing fishes from the main river and the many tributaries that poured into the Ohio.

Another unfortunate event occurred along the way. Rafinesque spent a protracted time with the now-famous bird artist John James Audubon, who lived near the Ohio River in Kentucky. Rafinesque wore out his welcome, setting off events that damaged his standing as a scientist.

Bats flew into Rafinesque’s room one evening and the eccentric guest swatted the flying mammals with his host’s prized violin, ruining it. Audubon returned the favor by suggesting that Ohio River tributaries were populated with mysterious fish species. Rafinesque made the mistake of trusting Audubon, fell for the prank, and published descriptions of Audubon’s fake fishes — ten in all — without seeing them, in what is otherwise a seminal 300-page text, titled Ichthyologia Ohioensis.

The fake fish tarnished the polymath’s reputation and did not serve Audubon well, either.

Passing through the Chillicothe area, Rafinesque was taken by the multitude of Indian mounds and the earthen ceremonial structures that surely stimulated his interest in archeology. Rafinesque excavated mounds and prodigiously published papers in what few scientific journals and popular magazines existed at the time. He also self-published his own tracts.

Circleville’s postmaster, Caleb Atwater, who was also a lawyer, had his own ardent interest in the ancient Indian earthworks; he published his own papers and a book on the Adena and Hopewell cultures — but to the dissatisfaction of Rafinesque, who publicly criticized the man. Atwater, not taking kindly to the criticism, embarked on a letter-writing smear campaign, maybe with free postage, against his critic. It had the intended effect, impugning Rafinesque’s credibility, painting him as a crank and a sloppy scientist, a reputation that followed him to his grave in 1840.

Rafinesque did not always help himself. He professed to have deciphered the Walam Olum, a purported creation and migration story of the Delaware Indians who once inhabited Ohio. For decades, the Delaware Tribe accepted it as genuine. Modern scholarship in the late 20th century, however, revealed that Rafinesque perpetrated a fraud, actually translating English words into the Delaware language to create a believable but ultimately false story. Scholars surmise he hoped to gain a prize from an organization in Europe.

This much is true: The frenzied genius published 900 scientific papers and several books on topics of medicine, banking, archeology, and the Hebrew language. He named 6,700 plants, several species of turtles and mammals, including deer and coyote, and 26 fishes native to Ohio. Many organisms have since been named in his honor, including one you might find underfoot in slabs of limestone so common in Ohio. Specimens of Rafinesque’s eponymous genus of extinct brachiopods are fossilized in stone, a testament to a brilliant mind.

Constantine Rafinesque died in 1840 of liver cancer, perhaps brought on by herbal treatments he created

for himself.