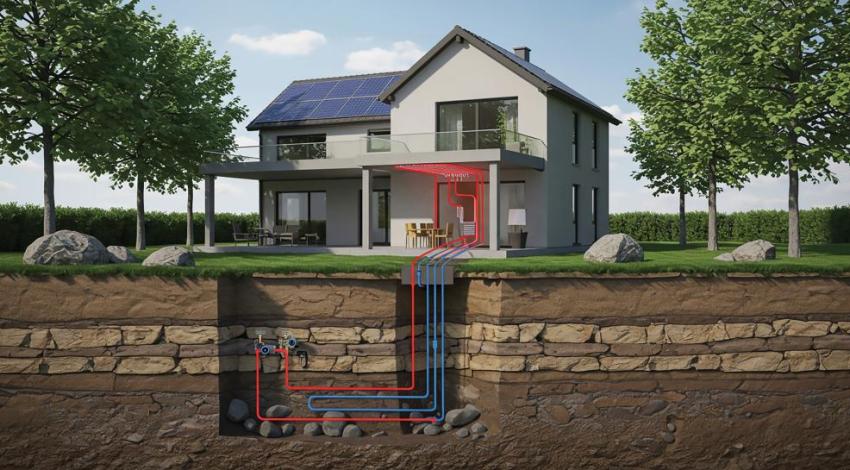

When people consider renewable energy sources, many people tend to look up. Solar power, after all, is a common choice for someone looking to go green or potentially save money on electricity.

“People choose geothermal for the environmental benefits and to save money,” says Tim Litton, director of marketing for WaterFurnace, an Indiana-based geothermal system manufacturer. “Geothermal is twice as efficient as any traditional heat pump, which means people can save more money on heating and cooling.