EDITOR’S NOTE:

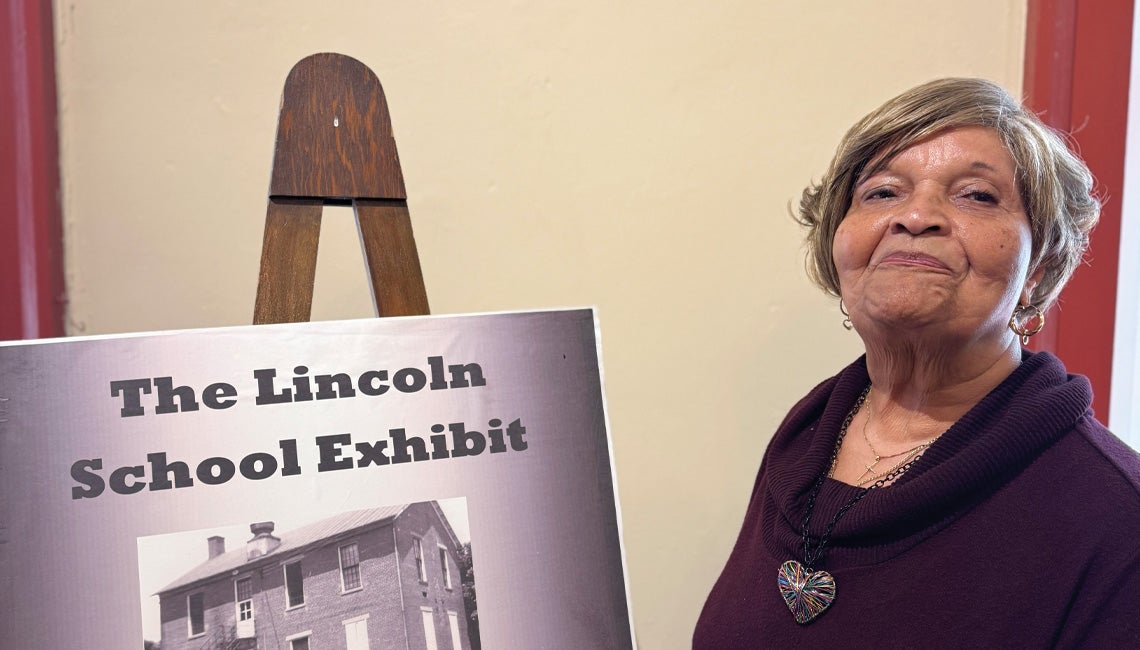

The Lincoln School Story is a powerful 30-minute film, produced with support from Ohio Humanities, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Ohio Arts Council. It tells the story of the Hillsboro mothers and children who, between 1954 and 1956, marched daily to demand an end to school segregation — making Hillsboro, Ohio, one of the first Northern tests of the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education. Developed in close partnership with the marchers and their families — including Eleanor Curtis Cumberland (pictured above), the daughter of the woman who led the marches — the film weaves together personal testimony, historical context, and archival photos to bring a little-known Civil Rights story into the national spotlight. The Lincoln School Story is available to stream for free at www.pbs.org.

It’s a quiet weekday afternoon in Hillsboro, the county seat of Highland County. School buses are everywhere. Older kids make their way home, carefree, backpacks swinging.

But going to school in this rural southwestern Ohio small town wasn’t always as easy, especially for Black children. The sidewalks they walk today were once part of a daily protest for the right to learn.

Imogene Curtis led the growing movement of mothers fighting for the rights of their children in Hillsboro. Although she herself hadn't finished high school, she became a powerful community organizer — writing letters, making calls, and rallying neighbors.

Separate and unequal

In its landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka decision, the U.S. Supreme Court declared “separate but equal” schools to be unconstitutional.

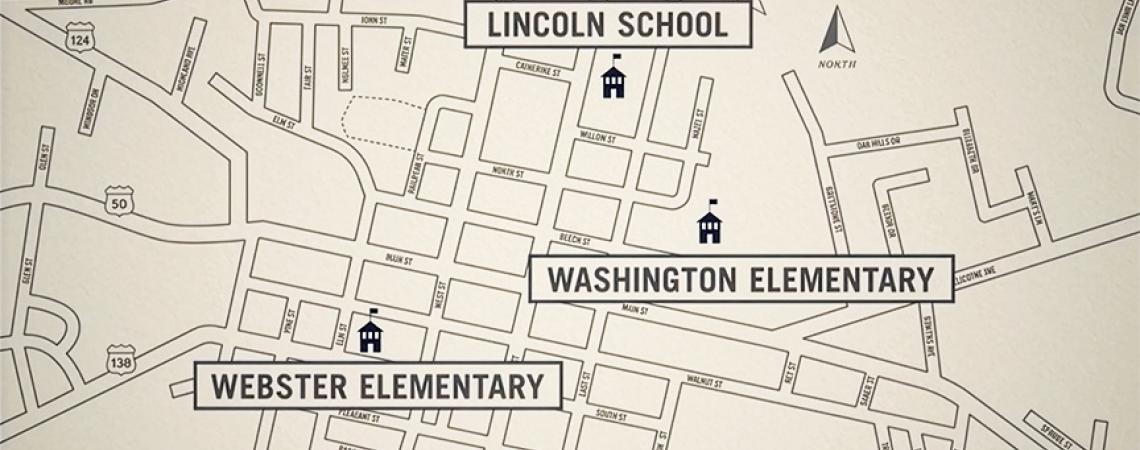

At the time, schools in Hillsboro (and many other places in Ohio and elsewhere) were segregated. Black children there were sent to Lincoln Elementary, on the east side of town. The building was crumbling. Classrooms combined three grade levels into one. Textbooks, when they had them, were often missing pages. In contrast, white students attended Webster and Washington elementaries, where math, science, and geography were part of a curriculum not provided to Lincoln’s students.

When the court ruling came down, Black parents in Hillsboro assumed their children would be allowed to enroll in the white schools that fall. But the local board of education stalled, keeping Black students at Lincoln.

What happened next became one of the longest sustained protests of the Civil Rights era.

At the start of the school year in September 1954, mothers and their children began marching every school day, from Hillsboro’s east end to the doors of Webster Elementary. They walked in all weather, through a daily assault of slurs hurled their way. Each day, the principal would greet them at the school’s entrance with the same answer: “Nothing has changed.” Then they would turn around and walk back home. They did this for nearly two years.

That fall, in 1954, five mothers refused to accept the delay. With support from the NAACP and the legal guidance of Constance Baker Motley and Thurgood Marshall, they filed a lawsuit demanding immediate integration. They would soon be joined by a growing number of mothers, led in spirit and strategy by Imogene Curtis.

Curtis was a housekeeper at the local VA hospital who led the march with her son at her side. Though she herself hadn’t finished high school, she became a powerful community organizer — writing letters, making calls, and rallying neighbors.

“I was just proud of my mom, period,” says Curtis’ daughter, Eleanor Curtis Cumberland. “Because she was always helping someone. That’s just who she was.” Eleanor was too old to attend Lincoln by then (she had just started at the newly integrated high school) but she remembers the yellow notepad her mother carried around the house, full of names and next steps.

The marches continued until April 1956, when a federal court finally ordered Hillsboro to desegregate its schools. The marchers’ persistence became a blueprint for communities across the country, offering one of the first practical tests of the Brown v. Board decision.

Today, Cumberland is in her eighties, but her voice is strong, and her presence is commanding. She never misses an opportunity to share her mother’s story. It’s not just history to Cumberland — it’s a blueprint for how to live.

“If someone comes to me with a problem,” she says, “I will find a way to help. A lot of that is because of my mom.”

Curtis’ activism wasn’t confined to the Lincoln School fight. She became the vice president of the Highland County NAACP, helped people facing housing discrimination, and stood beside neighbors in court. She joined the 1963 March on Washington, where she witnessed the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech. Cumberland absorbed those values.

Decades later, she was the one with a bullhorn, standing on the courthouse steps during Black Lives Matter protests. She joined local group HARD — Hillsboro Against Racism and Discrimination — and raised her voice once again, now with her own sons and grandchildren beside her. These days, Eleanor volunteers at Samaritan Outreach Services, Hillsboro’s local food pantry, which operates on the exact location where Lincoln Elementary once stood.

Keeping history alive

In 2015, a small group gathered at the Highland County Historical Society to discuss the story of the Lincoln School in Hillsboro. Among them was Kati Burwinkel, a local resident who had never heard the story.

“I just left that meeting thinking, ‘This story has to be told — and it has to be told by the people who lived it,’” she says.

What began, then, as a small oral history project quickly grew. Burwinkel wrote grants and brought in Cincinnati-based filmmaker Andrea Torrice to lead a collaborative documentary effort. The group met regularly for two years, sorting through photographs, recording memories, and shaping the story that needed to be told.

The finished film premiered in 2017 in Hillsboro, alongside the opening of a permanent exhibit at the historical society. Word spread quickly. Screenings at the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center and other venues and a Washington Post article sparked national interest. PBS picked up the documentary, which now airs in regular rotation on stations across the country.

After the film’s release, the daughters of the Lincoln School marchers were invited to speak in the very courtroom where, decades earlier, their mothers had been denied the right to testify. The event was broadcast live from Cincinnati and streamed to judges in Dayton and Columbus. The women were seated at the exact same table where their mothers had once sat, silenced. This time, they were the honored guests.

When Cumberland rose to speak about her mother, her voice trembled with emotion; her words, however, were clear, eloquent, and powerful. Afterward, one of the judges stood. “Barack Obama appointed me to this court for life,” he said. “Until today, I did not know this story. And I am a changed person.”

Everyone in the room understood: History had come full circle. And this time, the world was listening.