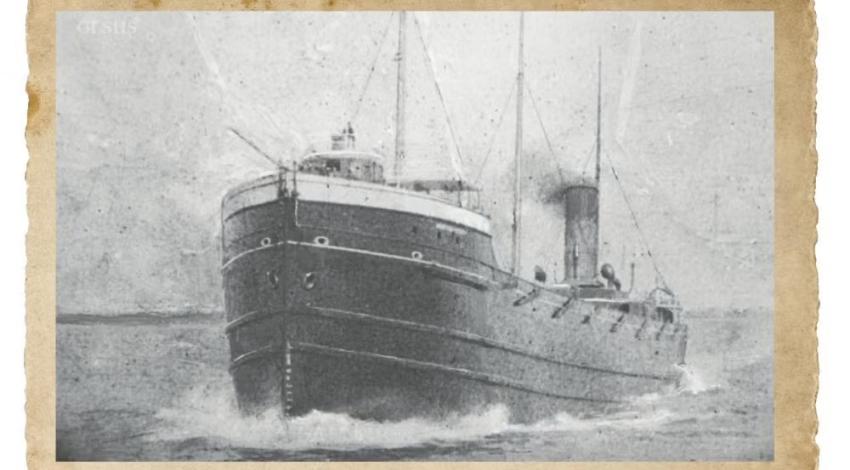

Decades ago, when I was a much younger man, I was a serious waterfowl hunter.

Large, handsome, fast-flying birds, canvasbacks were not exactly numerous during those years, but they were plentiful enough to be considered fair game. No matter how hard we hunted, however, we never bagged a single one.

I retired from duck hunting and sold the boat decades ago, but in truth, I never totally lost the desire to bag a “bull can,” as hunters call the male (or drake) canvasback. Recently, I realized that I’m not getting any younger, and I decided that if I’m ever going to do it, I should probably do it soon. And I knew exactly where to begin my “hunt.”