A multitude of boaters, anglers, swimmers, vacationers, sun-chasers, and thrill-seekers flocks to Lake Erie each summer. Most of them will have no idea of the activity taking place far beneath those waters.

For the past 65 years, nearly half a mile down, two massive salt mines have been extracting more than 3 million tons of rock salt per year for use to melt snow and ice on Ohio’s winter streets, roads, and highways.

The salt beds under Lake Erie, formed eons ago, can measure 40 to 50 feet thick.

The entrance to one of the mines, operated by Cargill, Inc., is just offshore from downtown Cleveland on Whiskey Island (so named when a distillery was built on the site in the 1830s). The second mine, operated by Morton Salt, is 30 miles farther east along the lakeshore at Fairport Harbor. The property and mineral rights under the lake are owned by the State of Ohio, but the mineral rights are leased to the two operators.

“Geologists believe that the salt beds formed eons ago when an ancient, relatively shallow saltwater sea covered what one day would become the Buckeye State,” says Chris Wright, Ohio Department of Natural Resources, Division of Geological Survey program supervisor. “As the waters continually ebbed and flowed in the warm tropical climate, evaporation occurred, leaving salt beds that today in some parts of Ohio measure 40 to 50 feet thick.”

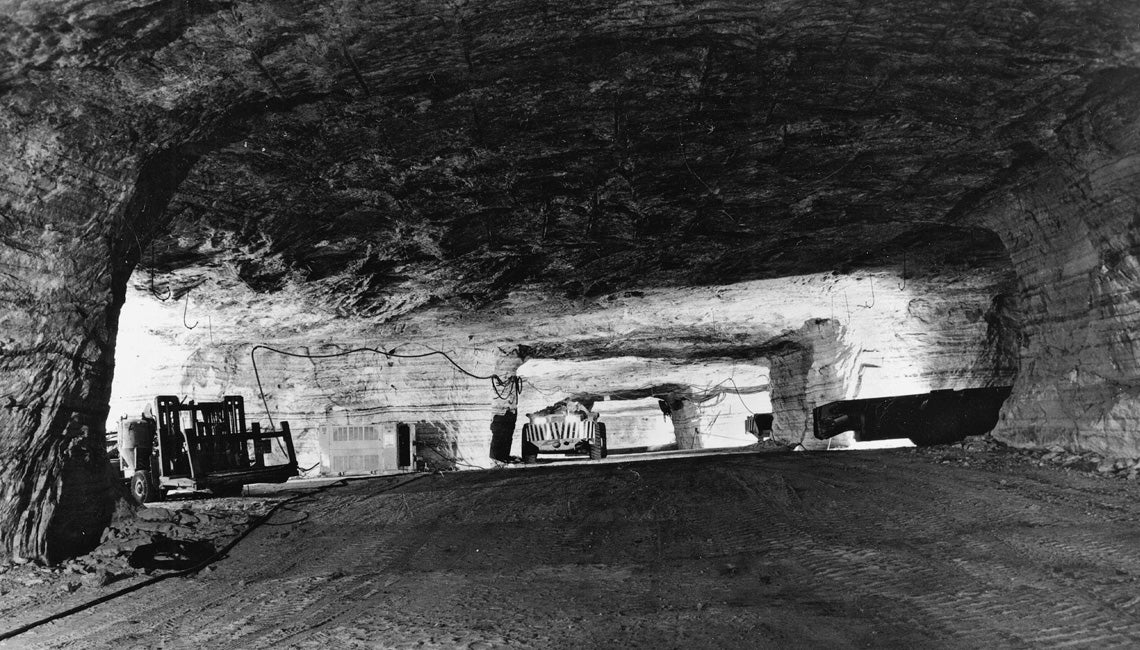

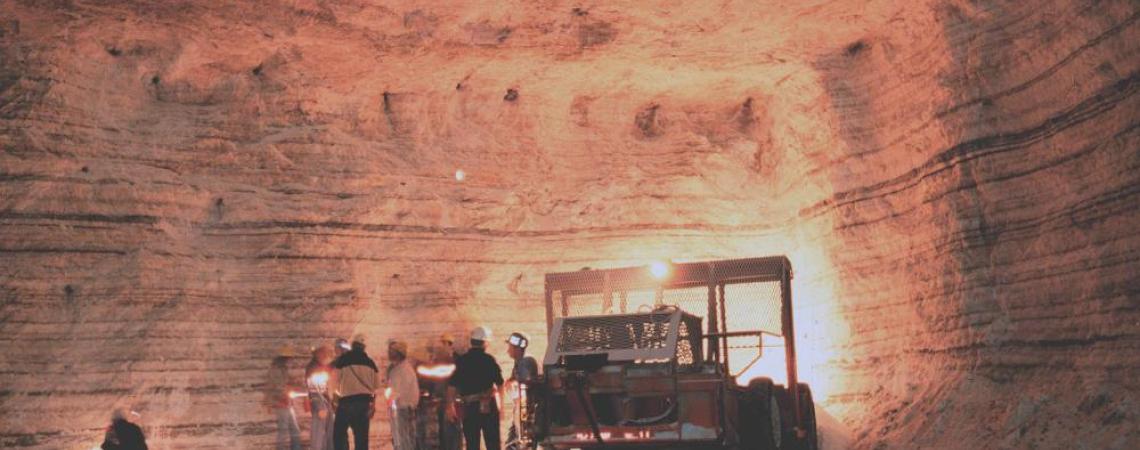

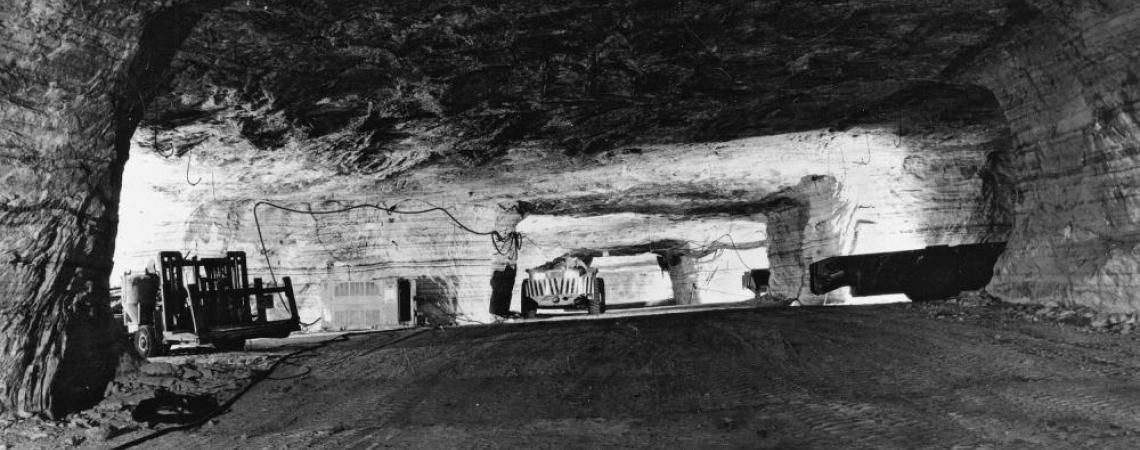

The construction of the two mines took place during the late 1950s; the initial vertical shaft of each mine, sunk to a depth of about 2,000 feet and measuring about 16 feet in diameter, took about two years to complete. At that depth, the shafts take a 90-degree turn, heading north under the lake bed.

Today, the horizontal mine passageways extend several miles under the lake. The large, powerful equipment needed to mine the salt — trucks, front-end loaders, conveyors, etc. — was lowered into the mines by first disassembling the machines into their component parts, then reassembling them at the bottom of the shaft.

The salt beds cover a vast area that includes most of eastern Ohio, western Pennsylvania, western New York, southwestern Ontario, central Michigan, and into northern West Virginia. So, why are the two Ohio mines located on the Erie shore?

“The answer is twofold,” Wright says. “Even though various salt layers can be found over a huge area, in Ohio they are closest to the surface along the lakeshore, making it more cost-effective to mine there. And secondly, it was much simpler for the operators to acquire the mineral rights from one entity — the State of Ohio — than deal with the many, many individual landowners who would have needed to be contracted inland.”

The mining itself is accomplished using what’s known as the room-and-pillar technique, in which about half of the salt in a particular “room” is removed, leaving a passageway, and the other half is allowed to remain in place as support pillars for the ceiling. To loosen the rock salt at the working face of the mine, small-diameter holes are drilled about 10 feet deep into the salt, spaced every few feet. Explosive charges are placed into the holes and detonated, and the loosened salt can then be scooped up, placed in trucks, and moved to the conveyors that take it to the main shaft and eventually to the surface.

Shallow mines are a lot like caves, which usually remain at the median temperature of the environment surrounding them. For example, Ohio Caverns near West Liberty is 103 feet deep and is a constant 54 degrees year-round, which is the median temperature for that part of Ohio.

“The natural temperature within the deeper salt mines is also relatively constant,” Wright says. “About 70 degrees, with the temperature actually warming a few degrees as you descend deeper and deeper underground, due to geothermal heat.”

An interesting side note is that the salt beds in the mines are constantly “flowing,” according to Wright — albeit at a literal glacial pace. Because of the extreme pressure of the rocks above the salt beds, the rock salt attempts to fill the empty spaces where salt has already been mined. As a result, some sections of the mines are no longer safe to enter because they have become unstable.

“There is no danger of cracks reaching all the way up to the bottom of Lake Erie and allowing the lake water to suddenly flood the mines,” Wright says. “It’s really nothing to worry about.”

W.H. “Chip” Gross is Ohio Cooperative Living’s outdoors editor. Email him with your outdoors questions at whchipgross@gmail.com. Be sure to include “Ask Chip” in the subject of the email. Your question may be answered on www.ohiocoopliving.com!