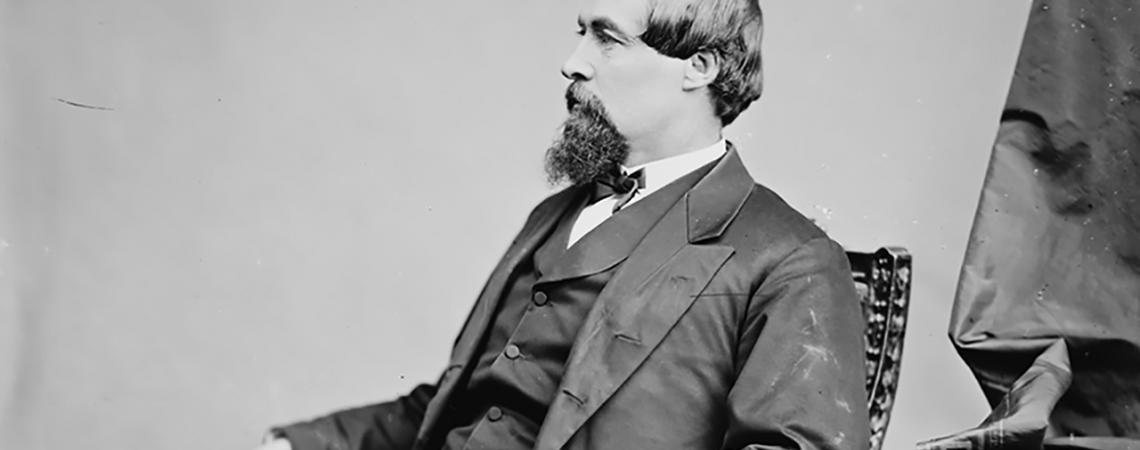

Edmund G. Ross (Credit: National Archives)

The year 1868 was one of turmoil and uncertainty in this country, when the very Union itself was in crisis. One man’s act of valor — not on a battlefield, but in a legislative body — may have been the deciding factor that held the nation together.

Edmund G. Ross cast the deciding vote in the staid United States Senate to acquit the impeached President Andrew Johnson in May of 1868. The vote earned him the widespread scorn at the time. But his act of conviction — ignoring both attempted bribery and physical threats — put him on the right side of history.

In 1957, in his book Profiles in Courage, John F. Kennedy, then a senator from Massachusetts, portrayed Ross as a man of righteous certitude for that vote, which preserved the office of the president and avoided more upheaval in a time when the wounds of the Civil War were scarcely scabbed over.

Ross was born on a farm in Ashland County and came of age near the county seat, where a plaque with his name (misspelled) was mounted in his honor. He pursued a career in publishing — one that he kept at his entire life. His name was on the masthead at the Sandusky Mirror, where he worked side by side with his brother, Sylvester. Ross and his wife, Fanny Lanthrop, from Sandusky, made their way to Kansas, where Ross published anti-slavery newspapers.

Ross took up the abolitionist cause in the Civil War. He joined a Kansas regiment as avprivate, and left as a major. At the war’s end, Ross returned to Kansas and was appointed by the governor to represent the state in the U.S. Senate.

That was where Ross, a Republican, intersected with Johnson, a Democrat, who was facing charges of malfeasance. Johnson had removed Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, contrary to a law that had been passed specifically to prevent such an act by the executive. Ross viewed the law as unconstitutional. and he held to his conviction that the president should not be removed.

In turn, Ross paid a political price and was not returned to the Senate. He continued his career in publishing, however, which eventually landed him in New Mexico. President Grover Cleveland tapped Ross to serve a four-year term as governor of the New Mexico Territory in 1885.

Ross reflected on these events in his autobiography that he penned in Santa Fe after his term as governor: “I was again and very promptly relegated to private life and the printer’s case — and am now, by turns, printer, farmer, gentleman at leisure, author, philosopher and tramp — but never a sorehead.” The native Buckeye who helped hold the Union together lies at rest in northern New Mexico beneath a most underwhelming gravestone. He died in 1909.

Craig Springer writes from Santa Fe County, New Mexico, near where Edmond Ross spent his last days.