W.H. Chip Gross

North America’s prairies once stretched from the foothills of the Rocky Mountains east into western Ohio, a staggering 1 million square miles or more of native grasslands that covered a third to nearly half of our country.

But what took millennia to develop disappeared in only half a century. The transformation began in 1833, when John Lane Sr. created the polished-steel, self-scouring plow, which could penetrate heavy prairie soils. A fellow blacksmith then improved upon Lane’s original design and marketed the new plow aggressively. That second blacksmith was John Deere.

What is it that attracts us to lighthouses? Could it be their immovable stability in an ever-changing world? Mute guides to somehow show us the way, much as they do for wayward sailors?

Whatever the reason, people have been visiting the Marblehead Lighthouse on Lake Erie at the mouth of Sandusky Bay for nearly two centuries, ever since its construction in 1821. It’s the oldest lighthouse in continuous service anywhere on the Great Lakes.

A journey into America's 18th-century eastern frontier

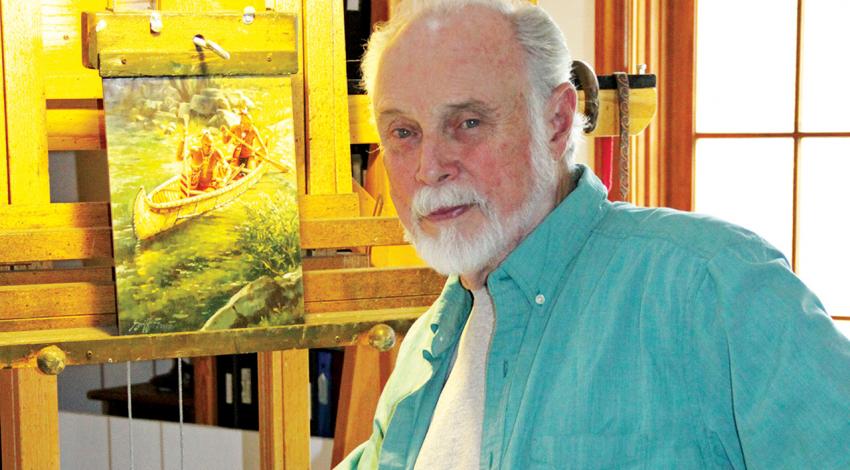

Where others see modern-day cities, he sees ancient Indian villages. Where others see today’s crop fields, he sees vast virgin forests. In short, Robert Griffing sees Ohio as it was long before it ever became a state. He also sees — and paints — the Native American people who lived here more than 250 years ago.

Where others see modern-day cities, he sees ancient Indian villages. Where others see today’s crop fields, he sees vast virgin forests. In short, Robert Griffing sees Ohio as it was long before it ever became a state. He also sees — and paints — the Native American people who lived here more than 250 years ago.

During the early 1800s, Ohio was the western edge of America’s frontier. A few Native American tribes still remained in the state, but the Indian Removal Act numbered their days. Passed by the U.S. Congress in 1830, the Act required all Indians living on reservations to move west of the Mississippi. The last to leave the Buckeye State were the Wyandot, and the man tasked with making that happen was John Johnston (1774–1861).

Some of the best birding in all of North America takes place in the marshes, seasonal wetlands, and swamp forests bordering western Lake Erie. At the heart of that region sits Ottawa National Wildlife Refuge (ONWR), home to everything from huge trumpeter swans with 8-foot wingspans to tiny, colorful wood warblers weighing mere ounces.

I admit it: I’m hooked on fishing. Like most addicts, I like to believe I can quit at any time — just walk away. But deep down I know that’s not true. We fishermen even have an expression to explain our illness: “The tug is the drug.”

Last April, for instance, I was fishing the Detroit River, which is always cold in early spring. Even though the air temperature was in the low 50s that morning, high winds had 2-foot waves white-capping the 42-degree water, and it felt like winter.

It’s easy to find Joe Bodis’s property in Huron County, a few miles southeast of New London, Ohio. Just look for the house surrounded by “weeds.”

In actuality, those “weeds” are a carefully planned and developed island of wildlife habitat in a sea of corn and soybean fields. “When I first moved in, neighbors used to stop and ask when I was going to mow the weeds,” Bodis says. “Now they ask what things they can do on their property to attract wildlife.”

A retired pharmaceuticals salesman and member of Firelands Electric Cooperative, Bodis moved to his 5 acres in 2002.