When the Cleveland Indians changed their name to the Cleveland Guardians last year, the rebrand was more than a tribute to the stalwart, Art Deco-style statues — known as the “Guardians of Traffic” — that grace the Hope Memorial Bridge near Progressive Field. It was also a reminder that one of the nation’s most beloved entertainers — Bob Hope — grew up in Cleveland and commenced his show business career there. “I left England when I was 4,” Hope once joked, “because I found out I could never be king.” Instead, he became America’s court jester.

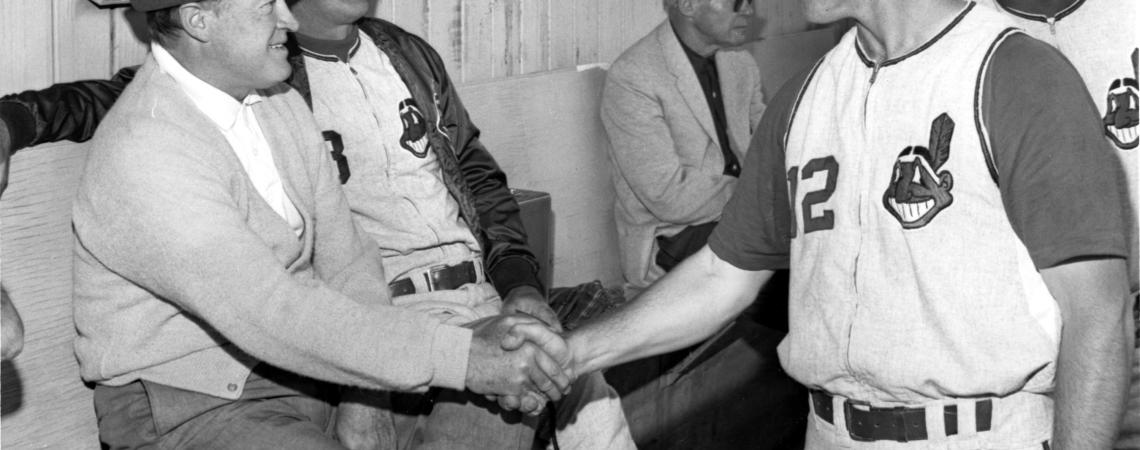

Bob Hope chats with Indians players during his time as co-owner of the team (photo courtesy of the Cleveland Guardians).

Born Leslie Townes Hope in a London suburb in 1903, Bob Hope was the fifth of the seven sons of English stonecutter William Henry “Harry” Hope and his wife, Avis. Harry brought his family to Cleveland in 1908, and in the early 1930s, he helped create the “Guardians of Traffic” for the city’s Lorain-Carnegie Bridge. After extensive repairs were completed in 1983, it was rechristened the Hope Memorial Bridge because of Harry’s work on the now-iconic “Guardians.”

The Hopes lived in Doan’s Corner, a bustling east-side neighborhood complete with commercial buildings, hotels, and vaudeville houses. Avis made ends meet by taking in boarders, and young Leslie earned money at jobs ranging from newsboy to taffy puller. He also hustled pool, spent time in reform school, and, after dropping out of high school, boxed under the name Packy East.

I came from a pretty tough neighborhood,” Hope later recalled. “We’d have been called juvenile delinquents, only our neighborhood couldn’t afford a sociologist."

As it turned out, Doan’s Corner was the perfect petri dish for nurturing the talents that took Hope from throwing punches to delivering punchlines. Despite his shenanigans, he sang in the choir at the Church of the Covenant — which Harry helped to build — on Euclid Avenue. Avis, who was a singer of Welsh heritage, took him to the Alhambra Theater’s vaudeville shows, and made sure he joined the Welsh community’s songfests at Euclid Beach. In 1915, Hope won a Charlie Chaplin impersonation contest at Luna Park and used his prize to buy Avis a stove.

Hope also took dancing lessons and convinced his girlfriend to be his partner. They performed on the city’s vaudeville circuit, but when the girl’s mother forbade her to go on out-of-town bookings, he resourcefully teamed up with a neighborhood chum. After years of honing his dancing, singing, and comedy skills in touring vaudeville and musical comedy shows, Hope transitioned to a solo act in 1928. He also switched his first name from the rather formal, British-sounding “Leslie” to the friendly, quintessentially American “Bob,” explaining afterward that he liked the “Hiya, fellas” quality it conveyed.

Hope eagerly did whatever it took to please audiences, and within a decade of reinventing his persona, he had crooned the Cole Porter standard “It’s De-Lovely” on Broadway, pioneered the art of the monologue on his hit radio show, and starred in the Hollywood comedy The Big Broadcast of 1938. In that movie, Hope introduced a tune — “Thanks for the Memory” — that won an Academy Award and became his signature song. And when the public embraced television in the 1950s, Hope started hosting network variety shows.

Going from gags to riches allowed Hope, who as a boy had watched Tris Speaker and Nap Lajoie through a knothole in the ballpark fence, to become part owner of the Cleveland Indians in 1946. As befits a great comedian, Hope’s timing was perfect, because the team won the 1948 World Series. In 1993, Hope returned to Cleveland for the Indians’ farewell game in Municipal Stadium. From the pitcher’s mound, the 90-year-old spoke affectionately about his hometown and sang a rendition of “Thanks for the Memory” that commemorated Bob Feller’s fastball and Al Rosen’s hits.

The crowd and players greeted Hope with a standing ovation that day. But their admiration reflected more than the fact that he was a Clevelander who had conquered every mass entertainment medium of the twentieth century or that his work with everybody from Bing Crosby and Lucille Ball to Big Bird and Brooke Shields had invariably tickled the nation’s funny bone. The performances that elevated Hope from household name to living legend were the USO shows that endeared him to generations of GIs. From World War II through the Korean, Vietnam, and Persian Gulf wars, Hope brought laughter to the front lines, and in recognition of the 50 years he spent boosting morale in the Armed Forces, Congress in 1997 made Hope the nation’s first honorary veteran.

With veteran status, Hope could have requested a gravesite in Arlington National Cemetery, and shortly before he died in 2003, his wife, Dolores, asked him where he wanted to be buried. Hope replied, “Surprise me.” A consummate trouper to the end, Bob Hope got the last laugh.