When young Gary Stretar wasn’t playing sports, he was busy drawing something. He didn’t grow up to become an athlete, but two childhood influences cemented that second pastime into a rewarding career.

Stretar grew up in the western suburbs of Cleveland. Inspired by proximity to Lake Erie, he painted mostly seascapes in watercolors. He took art classes in high school and college, but didn’t major in art. He preferred creating realistic art to styles of art that were popular at the time. Today, he displays his work in a gallery on his property, and travels to sell his works at various shows around the country.

While he credits his wife, Mary, also a talented painter, for improving his painting, it was two early influences that gave him his inspiration.

The first was his teacher in both fifth and sixth grades, Miss Paul. Stretar says he didn’t learn much more in college art classes than what Miss Paul had already taught him. “Teachers don’t always challenge kids to learn more, but she did,” he says. “She wasn’t afraid to teach us [advanced art techniques of] perspective, line, color values. A lot of us in her classes went on to art careers.”

The second influence was a schoolmate (and still friend) who invited Stretar to visit his family’s farm in Holmes County. Stretar ended up spending countless hours on that 150-acre tract, painting and visualizing. “It was a completely different world for me,” he says.

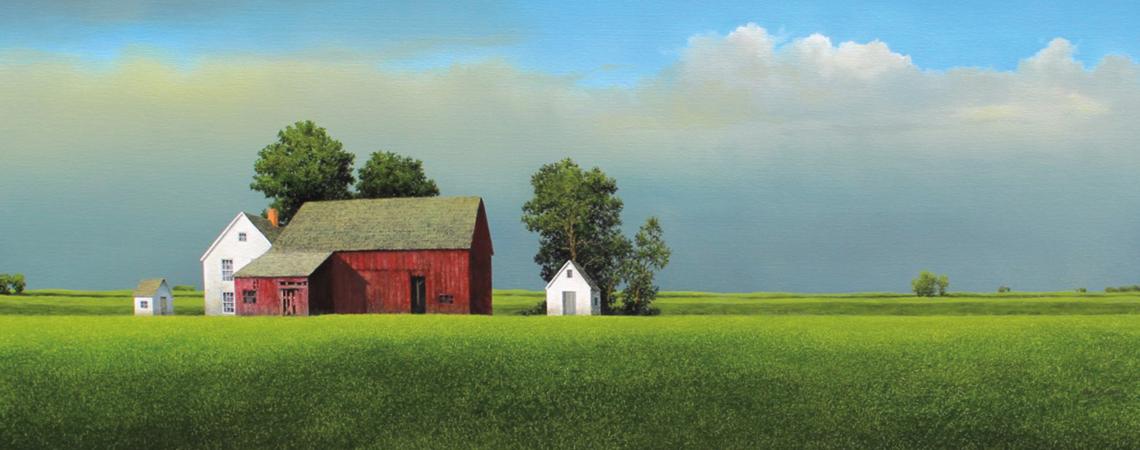

After the Stretars married, they continued living in the Cleveland area for a while, but they dreamed of one day living in an old house in the country. When they realized their dream and moved to a converted dairy farm near Spencer — where they are members of Lorain-Medina Rural Electric Cooperative — Stretar switched from painting those Lake Erie seascapes, mostly using watercolors, to painting rural landscapes, primarily in oil.

“I found that oils gave me more flexibility in what and how I could paint,” he says.

Stretar’s art studio is a converted dairy barn. Their 1835 Greek Revival house overlooks Mary’s extensive flower and vegetable gardens.

Many landscape artists set up their easels outside and paint their surroundings, a technique known as plein air, or they photograph a scene to paint later. Not Stretar. “Almost never do I paint [while] on-site,” he says. “And rarely do I photograph a scene to paint later.”

Instead, he makes a small, 3-by-5-inch sketch of what he wants to include in a painting. Then later, he starts painting scenes from memory. For authenticity of detail — such as the angle of a barn’s roof — he relies on the approximately 100 books on styles of rural architecture that he owns.

Stretar’s aim in his painting is “to make a farm look the way it did before the 1860s, so that early farmers would recognize it.”

His paintings portray farms before mechanization, when farmers used only oxen or draft horses. Because he doesn’t include people or animals, his art conveys both a sense of timelessness and a bit of mystery.

Stretar sells as many winter landscapes as he does paintings showing all the other seasons combined. He notes that “the winter color palette is closer to those of the Dutch Masters,” who influence his style of painting, along with painters of the Hudson River School and French Barbizon School.

Stretar says that the most rewarding part of creating his paintings is “when a client says that a painting ‘takes me back to when I was a child.’”

Besides their artist parents, the Stretars’ five children learned about art from their maternal grandmother. Her watercolor paintings became illustrations for many greeting cards.

Several of the Stretars’ children are full- or part-time artists today. Daughter Ruth, a hairdresser, sells her watercolors at her salon. Son Luke has his own painting studio in Richfield. Son Caleb is a sculptor and painter. “They had a great art teacher, Dean Shaffer, here at Black River High School,” Stretar notes.

To view Stretar’s paintings, visit www.garystretar.com. His gallery is open by appointment only.