A professor of biology and ecology at Ashland University, Merrill Tawse has been running the same wild-bird survey route annually for more than 40 years. It’s not for his work, though; it’s purely for pleasure.

“I look forward to it every year,” he says. “It’s great exercise and a break from my normal teaching routine. I guess I just enjoy stomping around outdoors any time of year.”

Known as the Christmas Bird Count, it’s a December tradition not only for Buckeye birders but for birdwatchers throughout the U.S. and beyond — from above the Arctic Circle to the southern tip of South America. Coordinated by the National Audubon Society, the annual CBC began more than a century ago, ironically, as a bird hunt.

Screech owl

Before 1900, rural people engaged in a holiday tradition known as the Christmas “side hunt.” Sides (teams) were chosen, and team members fanned out through the countryside with their rifles and shotguns. Whichever team amassed the most feathered or furred quarry by the end of the day won the contest.

As an alternative to those hunts, Frank Chapman, an early officer of the then-fledgling National Audubon Society, suggested a “Christmas Bird Census” that would record the number of wild birds present during the holidays, rather than hunt them. Thus, the Christmas Bird Count was born … er, hatched.

I joined Tawse and his lab assistant, Tyler Theaker, before dawn on a Saturday morning last December to tag along on a section of the CBC near Mansfield. With the temperature hovering around freezing and precipitation changing back and forth from wet snow to rain, the weather couldn’t have been much worse for birding. Nevertheless, Tawse and Theaker had already recorded six screech owls on their official list. Starting at 4 a.m., the pair had made about a dozen stops along the survey route, playing a loud recording of screech owl calls into the darkness that the real birds answered.

CBC survey areas are 15-mile-diameter circles, and there are 75 of them scattered across Ohio. Teams of birders volunteer their time to identify as many wild bird species as possible within those circles — by sight or sound. The observations are made over a 24-hour period anytime during a three-week window from mid-December through early January.

Tawse calls it “citizen science,” with the birding among groups friendly, yet intense. An air of competition pervades to see which group can see not only the most species of birds but also the most unusual. We spotted about 30 species during our half-day of tallying, including a pair of Virginia rails, an effort Tawse pronounced “good for the weather conditions.”

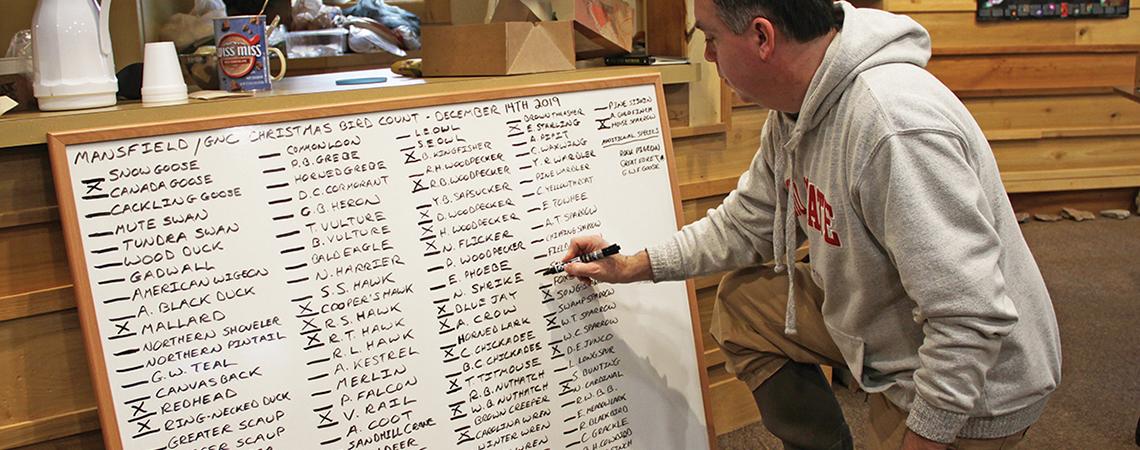

At noon, we headed for Gorman Nature Center near Mansfield to warm up with a bowl of hot chili as we conferred with members of the other teams and compiled a master list of birds observed that morning. The list would eventually be submitted to the Audubon Society’s national office and added to its database.

When asked what changes he’s noticed in wild bird populations over the years, Tawse mentioned a general decrease in avian numbers overall, especially with grassland species in Ohio such as meadowlarks and ring-necked pheasants. He was quick, however, to mention an encouraging trend.

“When I began participating in the CBC during the 1980s, there were only four bald eagle nests in the state,” he said. “Today, there are more than 700 nests, and the population of eagles continues to soar.” How appropriate then, it seemed, that the final two birds we added to our list last December were a pair of mature bald eagles.

You don’t need to be an expert birder to participate in the Christmas Bird Count. If you feel less than confident in your bird ID skills, you will be matched with accomplished birders, which is a great way to learn. Young people are also encouraged to participate; last year, members of the Lexington High School Biology Club assisted on some of the Mansfield CBC survey routes.

Click here to contact a Christmas Bird Count coordinator near you or call your local nature center.