Like most wildlife photographers of the early 20th century — though there were only a handful — Karl Maslowski was a hunter before he became a photographer. “The things I’d learned about hunting wild animals with a gun stood me in good stead as I began hunting them with a camera,” he said.

The son of immigrant parents who’d arrived in America from Europe in 1911, Maslowski was born in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1913. Two years later, the family of three moved to Cincinnati, and he would call the Queen City home for the rest of his long life.

It was in 1935, during the middle of the Great Depression, when 22-year-old Maslowski scraped together enough money to buy his first camera. A used, bulky Graflex, it cost $8 and shot black-and-white still photos. But it was a start, and with that camera, Maslowski taught himself the basics of photography. He also soon learned that the short lenses and slow shutter speeds of such cameras were no match for quick-moving wildlife.

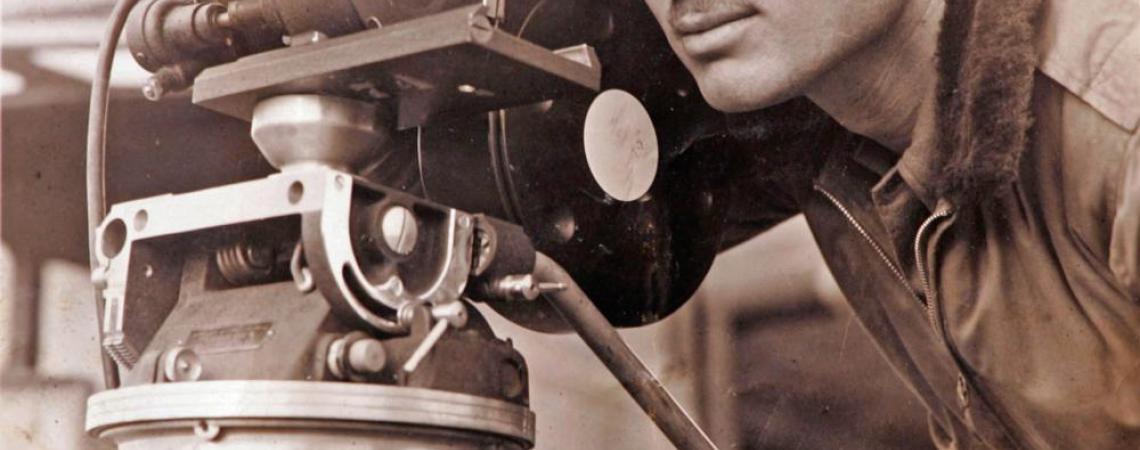

Karl Maslowski served as a combat cameraman for the U.S. Army Air Forces during World War II. He filmed aircraft and camp life at an airbase in Corsica under famed director Capt. William Wyler. Some of Maslowski’s footage was later used in the 1947 film Thunderbolt!

The answer to his problem, he believed, was acquiring one of those newfangled 16mm movie cameras he had been hearing so much about. “But they were just too expensive, and our family was dirt poor,” Maslowski remembered. Fate, however, sometimes has a way of intervening in such situations.

Unsung benefactor

Maslowski had begun visiting the Cincinnati Museum of Natural History at age 15, fascinated by its collections of mounted wild animals. It was at the museum that Maslowski met Christian J. Goetz, head of the Christian Moerlein Brewery in Cincinnati and a major financial supporter of the museum. Goetz’s hobby was banding birds, mainly waterfowl, and Maslowski began tagging along with him on banding trips.

One day, Goetz casually asked Maslowski what type of 16mm movie camera would be best for photographing their banding activities. The young shutterbug knew exactly what Goetz needed: a Cine-Kodak Special. As a result, Goetz soon purchased one of the new movie cameras, handed it to Maslowski, and told him to “check it out for me, just to make sure everything’s working okay.” Goetz never asked for the camera to be returned. “Sadly, I didn’t realize what that kind, generous man had done for me until years later,” Maslowski admitted.

With the proper equipment now in hand, Maslowski threw himself into what he hoped would be his new career. Always energetic, he let no obstacle stand in the way of getting the wildlife photos he envisioned. For instance, along the shoreline of Lake Erie, he once constructed an 85-foot tower with a blind on top to film nesting bald eagles at eye level. At Reelfoot Lake in Tennessee, he built an even higher tower, 100 feet tall, to photograph nesting cranes, herons, and cormorants. The resulting unprecedented film footage was sold to high-end clients such as Walt Disney’s True-Life Adventure Series, which turned the footage into wildlife profile stories.

New ways to spread the word

Maslowski also eventually joined the professional lecture circuit, taking his wildlife films on the road nationwide. A gifted speaker with a strong, commanding voice, Maslowski mesmerized his audiences — always leaving them wanting more.

For the Audubon Screen Tour lecture series, Maslowski joined several other notable natural-history speakers — one of the more famous being Roger Tory Peterson, creator of the well-known field guide series. For the National Geographic Society, Maslowski regularly presented his film lectures in Washington, D.C.

There seemed to be no limit to his communication skills. In addition to his films, Maslowski wrote thousands of outdoors- and nature-related newspaper and magazine articles during his lifetime. The Cincinnati Enquirer ran his weekly “Naturalist Afield” column for half a century, from 1937 to 1988.

Well-earned recognition

Not surprisingly, Maslowski received many awards during his lifetime. Said one presenter: “He interprets to millions the learning of scientists in layperson’s language. All aspects of nature have received the scrutiny of his lenses.”

Near the end of his life, while reflecting on his fulfilling career, Maslowski said, “If I had to come back and live my life over as an animal, I’d want to come back as a red fox. They have outsmarted me so many times. If I had my wish, I’d come back and do the same thing to them.”

Karl Maslowski died in 2006 at the age of 92. His son, Steve, carries on his father’s legacy as an acclaimed wildlife filmmaker yet today. And, yes, the Maslowski film studio is still headquartered in Cincinnati.

To view Wildlife Photographer: The Life of Karl Maslowski, Steve Maslowski’s film tribute to his father, click here.