In the fall of 1935, in the depths of the Great Depression and the dawning of the New Deal, a young executive from the Ohio Farm Bureau Federation traveled to Washington, D.C., to meet Morris L. Cooke, director of the Rural Electrification Administration — a program crucial to the success of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s first-term economic recovery effort.

The rural electrification cause had helped FDR win the White House, and U.S. farmers were clamoring for power. The Farm Bureau wanted to help, and the organization sent its first executive secretary, Murray D. Lincoln, on a fact-finding mission to Washington months before Congress approved the government loan program to support Roosevelt’s vision.

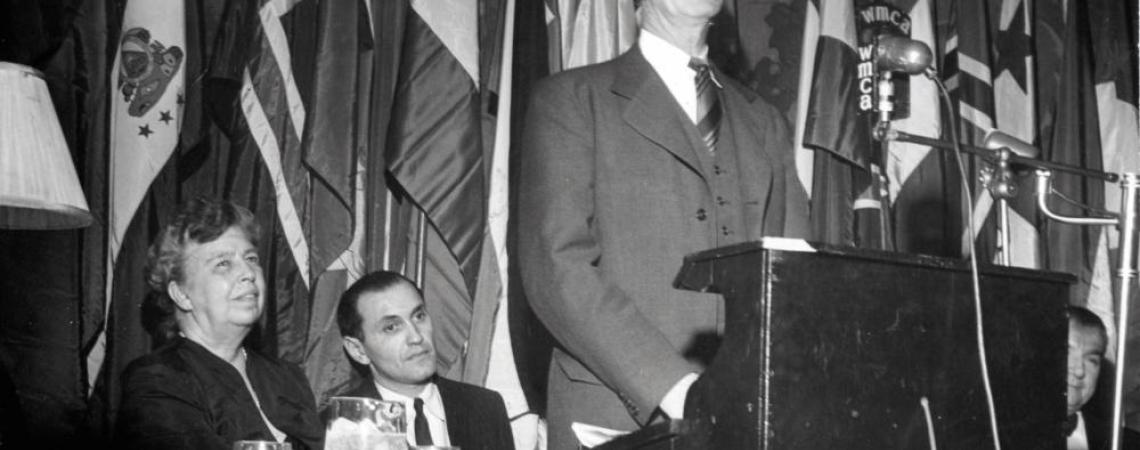

Murray Lincoln addresses an assembly gathered to hear about electrification, as Eleanor Roosevelt (left) listens intently.

The initial meeting didn’t go so well, as Lincoln remembers in his autobiography, Vice President in Charge of Revolution.

Shown into his office, I told him that we of the Farm Bureau wanted to avail ourselves of the benefits of this legislation and set up our own utility plants.

“What do you know about the utility business?” Mr. Cooke asked.

“Nothing,” I admitted cheerfully. “I was trained in dairying and animal husbandry.”

The story may well have been embellished for dramatic effect, but it captures the essence of what history remembers of Murray Lincoln: brash, confident to the point of hubris, and proud of his farm roots.

Born in 1892 on a small Massachusetts farm, Lincoln became a leader of the cooperative movement in the United States. He began his career as a county agent in New England in 1914, fresh out of agricultural college, urging farmers to organize associations to produce their own fertilizer and market their own milk.

Cooperatives, Lincoln believed, represented “something that prevents the average man from being smothered between Big Business and Big Government.”

He became the first executive secretary of the Ohio Farm Bureau Federation in 1920 and led the organization into a variety of cooperative enterprises, from grain elevators and farm credit to auto insurance.

As an agent of change for farmers’ lives, however, Lincoln’s most significant undertaking was probably helping to launch the electric cooperative movement in Ohio. President Roosevelt, who believed access to electricity was essential to modernizing rural America, got the ball rolling in 1935 with an executive order establishing the REA. It had been half a century since the Edison Electric Illuminating Company built the first electric grid to light Manhattan, and by 1930 more than 90 percent of U.S. homes in cities and towns had electricity, along with a growing selection of electric-powered appliances.

The story was different in rural America. Roughly 33 million Americans lived on farms in 1935, and their lives were distinctly different from those in urban areas. The majority lacked indoor plumbing and used outhouses, and fewer than one in five farm homes were connected to the electricity grid. Farmers milked their cows by kerosene lamp in the morning darkness and did most of their chores in the daylight.

It wasn’t that farmers didn’t want electricity. The private, investor-owned utility companies of the time refused to extend service into sparsely populated farm country, saying it wasn’t cost-effective. But they weren’t excited about the New Deal program either. Morris and the rest of FDR’s team originally believed they would accomplish electrification with the help of private companies, but the utilities balked. In Ohio, they pressured the General Assembly to block enabling legislation that would have allowed the federal funds to flow to the states.

Lincoln and the Farm Bureau offered to set up rural electric cooperatives, which unleashed a battle with the private utilities that the co-ops eventually won, but not without political gamesmanship and wild tactics that Lincoln, who could be a bit pugilistic, seems to have relished. The private utilities managed to push legislation through the Ohio General Assembly that prevented the co-ops from crossing established utility lines, and then deliberately strung lines — as fast as possible — over the cooperatives’ planned routes.

Sometimes, the private utilities didn’t bother to secure rights-of-way from landowners, Lincoln recalled, and many of those landowners were farmers.

“When the poles went up, the farmers got together and chopped them down. The utility people came back and put them up again and, again, the farmers chopped that down.”

Despite the drama, Lincoln and his farm partners established more than 20 cooperatives within months, moving much faster than other U.S. states. As a result, Ohio received more than $5 million of the first $5.5 million approved by the REA.

A new subsidiary, the Farm Bureau Rural Electrification Cooperative, Inc., was formed to oversee the buildout. They bought their power from municipal power plants and built the lines at less than half the cost of the private companies. By 1937, the cooperatives had more than doubled the percentage of farm homes connected to central electricity. A dozen years later, more than 90 percent of farms had power.

By then, the Farm Bureau was no longer involved, having passed the baton, in 1942, to a new, independent organization, Ohio Rural Electric Cooperatives, Inc. Today, 25 electric cooperatives serve more than 400,000 homes and businesses in 77 of Ohio’s 88 counties.

“I believe that the rural electric cooperatives … are among the most dramatic demonstrations of the power of the cooperative concept that this country has ever seen,” Lincoln wrote in his autobiography, “and I am proud to say that I had a share in their conception, beginnings, and early days.”