Jennifer Aultman speaks with reverence when she talks about Ohio’s earthworks — eight of which, linked together as the Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks, have been inscribed as a World Heritage Site by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). The designation goes to places with “cultural and/or natural significance which is so exceptional that it transcends national boundaries and is of importance to present and future generations of all humanity.”

“(The designation) is this concept that there are places, no matter what side of a country’s borders they fall on, that should matter to all people,” says Aultman, chief historic sites officer at Ohio History Connection, which manages three of the eight earthworks included as a single site on the U.S. World Heritage application (the others are managed by the National Park Service).

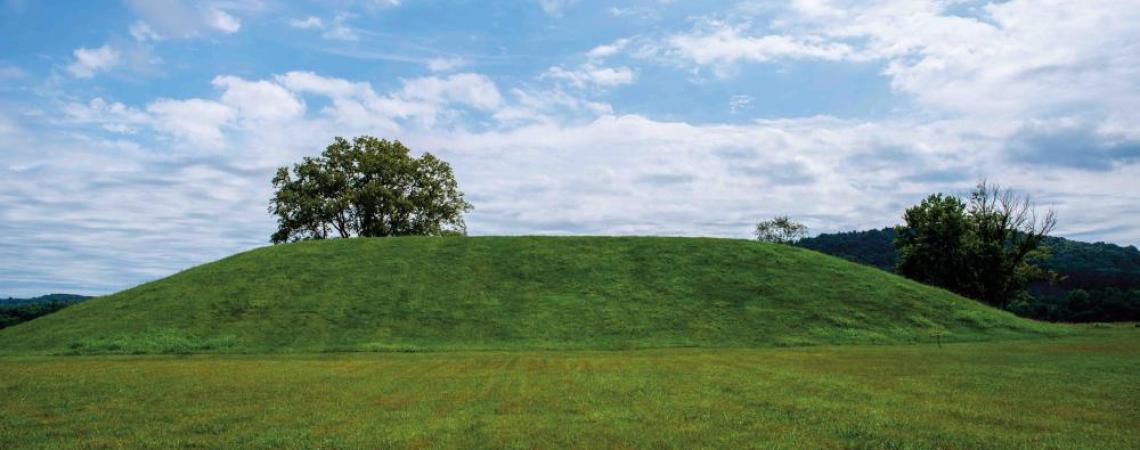

The reconstructed Central Mound at the Seip Earthworks southwest of Chillicothe (photograph by Mary Salen/Getty Images).

About 1,100 landmarks around the globe have been added to the list since the program began in 1972, with 25 of them in the U.S. This is the first in Ohio.

Why are they special?

There are 10 criteria, any one of which qualifies a site for the World Heritage list. The OHC/NPS team cited two of those as they made the case for the Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks.

First, they argued that, considering their size, geometry, and precise astronomical alignment, the Hopewell earthworks are “masterpieces of human creative genius.”

“They have very specific geometry,” Aultman says. “They have nearly perfect circles, and you can see the same exact sizes of circles repeated across Ohio. They’re not by accident. Those measurements mattered — for reasons that we don’t understand, but they mattered.”

What makes them even more impressive, Aultman says, is that the enormous walls, mounds, and shapes were built by people using simple digging tools like clam shells or deer scapulas attached to the end of sticks, yet they form geometrically precise squares, circles, and octagons that align perfectly with the complex cycles of the sun and moon. “They put earth into woven baskets and moved it one basket at a time to build the walls,” Aultman says. “When you consider the human undertaking and the commitment, it’s pretty incredible.”

The second criterion that scored the UNESCO designation was that the earthworks bear “exceptional testimony to a cultural tradition.”

“(Hopewell-era people) were bringing ceremonial objects and materials to the Ohio River Valley from across two-thirds of North America,” Aultman says. The earthworks, for example, contain blades of obsidian from what is now Yellowstone National Park, grizzly bear teeth from the Rocky Mountains, shells from the Gulf Coast, and copper from Southern Canada. “We know that these items weren’t traded. It appears that people were bringing things for a spiritual movement.”

How did it happen?

It’s not easy to earn the World Heritage Site designation. Each UNESCO member nation maintains a list of tentative nominees, and after a five-year research and evaluation process that began in 2003, the Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks was officially added to the U.S. tentative list by the U.S. Department of the Interior in 2008. The U.S. selects one site per year from the list for formal nomination.

Ohio History Connection and the National Park Service worked on the Hopewell application for a decade before they were invited to put together a formal nomination in 2018. The State Department hand-delivered the proposal in the midst of the pandemic to Paris, where it was then vetted for authenticity and integrity. The nomination was officially put forward to the World Heritage Committee in January 2022.

Finally, late last year, a delegation that included representatives from American Indian nations, including the Seneca, Miami, and Wyandot — all of which are descended from the Hopewell-era people who built the earthworks — along with Ohio History Connection staff, and representatives from the Hopewell Culture National Historic Park in Chillicothe traveled to Saudi Arabia to present the application to the World Heritage Committee, a group of representatives from 21 countries that meets once a year to render final decisions. Spoiler: It was approved.

“It was incredibly hard to believe and process that it had actually happened,” remembers Aultman. “[Chief Glenna Wallace of the Eastern Shawnee Tribe] started speaking about how important this is to her and to indigenous people generally, and that’s when I started to realize the enormity.” Delegates from around the world showered the U.S. delegation with congratulations. “I get teary,” she says. “I was elated and incredibly humbled.”

What now?

So what is the impact on Ohio? As Aultman points out, “There’s not a big pot of money” that goes along with the designation — “not a dime.” But Dan Moder, executive director of Explore Licking County and incoming board chair for the Ohio Travel Association, says that it could have larger implications for state tourism.

“There are 85 other counties in Ohio that have other cool things,” Moder says. “There is renewed or brand-new interest in how to take the visitor to Ohio and keep them in Ohio as long as we can. As time goes on, we will see a lot more collaboration from county to county. It’s exciting.” Two other Ohio sites are among the 18 that remain on the U.S. tentative list: the Serpent Mound in Adams County and a set of four sites in Dayton that are associated with the Wright brothers’ pioneering efforts in human flight.

Aultman says the designation is already changing the way Ohioans are thinking about mounds that exist across the state.

“[Hopewell earthworks] are but a few among hundreds and hundreds of earthworks spread all over central and southern Ohio,” she says. “If you grew up in Portsmouth or Marietta, for example, you may think that everywhere is like that. But in the past few months, you hear that these places are really unique and it’s shifted people’s thinking. Communities that have earthworks are suddenly aware that theirs are connected to something that’s globally significant. It allows them to consider preserving and honoring them.”

What are they?

The Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks, recently inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, actually comprise eight separate works that span locations in Licking, Ross, and Warren counties.

They were constructed between 1,600 and 2,000 years ago by the original inhabitants of North America — the ancestors of the indigenous people whom Europeans met when they arrived here. The sacred sites were places of ceremony that drew gatherings of visitors from across the continent.

Newark Earthworks

Two separate works, each managed by the Ohio History Connection, lie less than 2 miles apart in Licking County and form the largest set of geometric earthen enclosures remaining in the world. Together they have been named Ohio’s official state prehistoric monument.

Nearly four football fields in diameter, Great Circle Earthworks is so large that it touches both the cities of Newark and Heath. Its walls are between 8 and 13 feet high, and the ring has a bird-shaped mound known as the Eagle Mound in its center. The circle is large enough that the Great Pyramid of Giza could fit inside its walls.

Less than 2 miles away sits the Octagon Earthworks in Newark. An architectural feat of astonishing precision, it consists of a 50-acre octagon connected to an almost-perfect 20-acre circle with a stone platform known as the Observatory Mound on the outer ring. The entry points align perfectly with the extreme rise and set points of the moon’s 18-year cycle.

The grounds of both are open year-round from dawn until dusk, though access to the Octagon Earthworks is limited because the land has been home to Moundbuilders Country Club since 1910. (Removing the golf course was a requirement of including the Octagon Earthworks in the UNESCO application, and the Ohio Supreme Court has ruled that Ohio History Connection, which has owned the land since 1933, can terminate the country club’s lease through eminent domain.) There is a museum and visitors center at the Great Circle, open 10 a.m.–4 p.m. Thu.–Sat.

Fort Ancient Earthworks

Built on a steep bluff overlooking the Little Miami River, Fort Ancient Earthworks and Nature Preserve is Ohio’s oldest state park, managed by the Ohio History Connection. It doesn’t have the geometric structures the other sites have; rather, its 3½ miles of earthen walls — some as high as 23 feet — enclose a 100-acre irregular-shaped plateau above the Little Miami River. It’s the largest hilltop enclosure in North America, but while the name suggests that this site was used as a defensive structure, evidence shows that it, too, was a ceremonial gathering place and astronomical observatory. The park grounds and visitors center, 6123 St. Rte. 350, Oregonia, are open 10 a.m.–5 p.m. Wed.–Sat. and noon–5 p.m. Sun. Admission is $7, under 6 free.

Hopewell Culture National Historical Park

Five earthworks in the UNESCO group make up the Hopewell Culture National Historical Park in and around Chillicothe, managed by the National Park Service.

Mound City is the centerpiece of the Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, having become a national monument in 1923. It consists of 25 mounds of various shapes and sizes enclosed by a low wall in an area just over the size of 10 football fields. All the mounds that are present are modern restorations based on intact base layers and early surveys of the site.

While most Hopewell complexes were seemingly used for less than two centuries, evidence suggests that the 111-acre Hopewell Mound Group maintained its significance as a ceremonial center throughout the entire era of the Hopewell Culture, about 400 years. It was the site of the largest mound of the Hopewell world.

Hopeton Earthworks, directly across the Scioto River from Mound City, has been almost completely eroded by modern agriculture, but the locations of its original walls and mounds have been revealed by modern, scientific archaeology and are made visible by interpretive planting and mowing of the site by the National Park Service.

The shapes that make up the Seip Earthworks — two enormous circles and a square — use precisely the same dimensions as four other earthworks in the Paint Valley area around Chillicothe, suggesting a common unit of measurement among the Hopewell-era people. What’s left of the Seip works has been largely unexplored.

What’s most astonishing about the High Bank Works is that it was constructed with the same design as the Octagon Earthworks 64 miles away in Newark — the circles of each, in fact, are the exact same size — but the with the axes rotated at exactly a 90-degree angle to one another. High Bank is currently a research preserve, open to the public only by special arrangement with the National Park Service.

All of the park grounds except at the High Bank Works are open to visitors from dawn to dusk every day. The main visitors center for the National Historical Park is at Mound City, 16062 St. Rte. 104, Chillicothe, and is open 9 a.m.–4 p.m. daily. Facilities vary at the other locations.