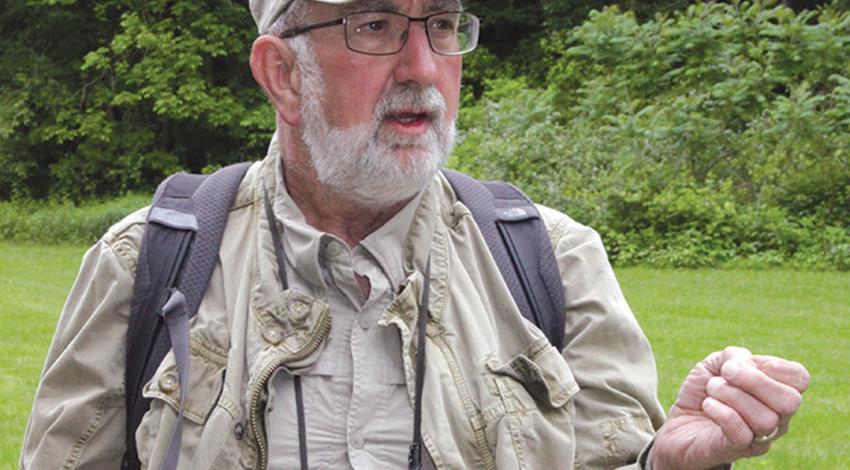

A professor of biology and ecology at Ashland University, Merrill Tawse has been running the same wild-bird survey route annually for more than 40 years. It’s not for his work, though; it’s purely for pleasure.

Before 1900, rural people engaged in a holiday tradition known as the Christmas “side hunt.” Sides (teams) were chosen, and team members fanned out through the countryside with their rifles and shotguns. Whichever team amassed the most feathered or furred quarry by the end of the day won the contest.