Emily Bania has been a member of an electric cooperative for as long as she can remember. Growing up around Belle Valley, she and her family were members of Marietta-based Washington Electric Cooperative.

When she married her husband, Matthew, they moved to their place between Pleasant City and Sarahsville, in northern Noble County, where they still live with their kids, Kora and Lane. They have remained members of Washington Electric for the past 10 years. “It’s just what we’ve always had,” Emily says. “We’ve always just appreciated being members. We know several people who work for the co-op, including one of our neighbors, who’s a lineman. They’re always friendly and helpful and I haven’t given it much thought past that.”

Matthew and Emily Bania, with their children, Kora, 5, and Lane, 2, live between Pleasant City and Sarahsville in rural Noble County. Their home is served by Washington Electric Cooperative. (Photo courtesy of Emily Bania)

Emily’s story is typical for co-op members. They get their electricity from, and pay their bills to, one of Ohio’s 25 electric distribution cooperatives; usually vote in the election for the co-op’s board of directors; and maybe attend the annual meeting of members. They might even get capital credits in the form of a check or a bill credit at the end of the year when the not-for-profit co-op’s revenues outpace its expenses.

It’s also typical for members not to think much about why their home or business gets electricity from a cooperative and not from one of the investor-owned utilities that operate in Ohio.

Co-ops, in fact, only came into being because the large, for-profit electric companies had no interest in stringing power lines out to farms and other rural areas — there was little or no profit to be made from doing so.

So, the farmers did it themselves. Thanks to the New Deal’s Rural Electrification Act back in the mid-1930s, funding became available for local co-ops to form and build out the infrastructure needed to turn on the lights on farms and in hamlets that were ignored by the power companies.

The first electric cooperative pole in the nation, in fact, was set by Piqua-based Pioneer Electric Cooperative in 1935, when only one out of every 10 rural Ohio farms and homes was electrified. By June of 1937, more than 36 percent of rural Ohio had electricity, and by 1950, it was almost 100 percent.

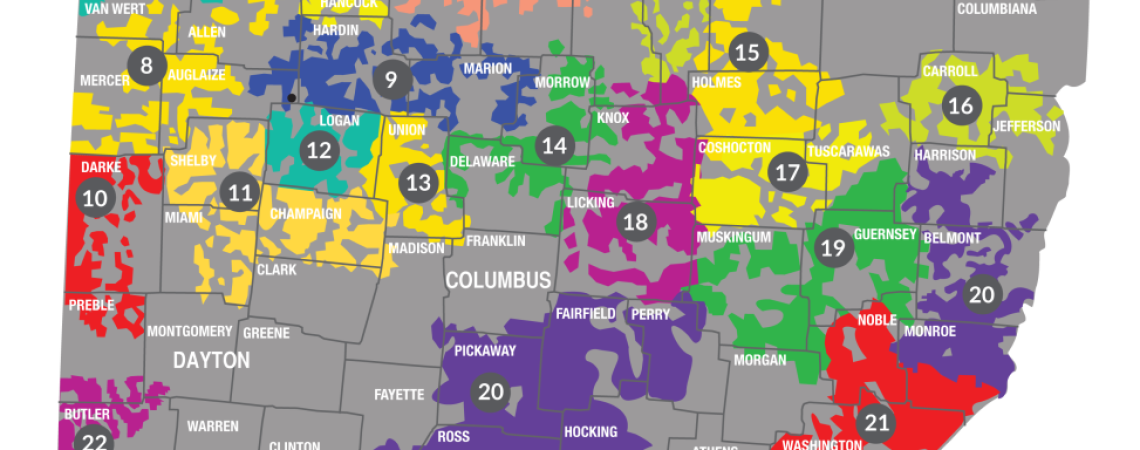

There have been as many as 57 distribution cooperatives in Ohio since that time. Through mergers or attrition, 25 still operate within the state. (West Virginia’s one co-op is a member of Ohio’s Electric Cooperatives, which provides shared services such as Ohio Cooperative Living magazine; Michigan-based Midwest Energy and Communications serves 1,000 members in northwestern Ohio.) Click here to view a map and list of Ohio's 25 electric cooperatives.

The co-ops determined the areas they’d serve when they formed, mostly based on geography and whether service was available from anyone else. Those territories remained mostly constant, though they were not legally defined. The situation led to some areas of overlapping service, which not only created confusion and safety issues, for example, for first responders arriving on an accident scene, but made it difficult for the utilities to plan for future growth.

Then in 1978, co-ops banded together to push the Ohio Legislature to pass House Bill 577, which defined service territories and mandated the Public Utilities Commission to certify the areas where each electric provider in the state has both the obligation and exclusive right to provide electric service. The legislation protected both co-ops and consumers, who could no longer be denied service for simple reason of convenience to the electricity provider. With the publication of the PUCO map, all co-ops, municipal systems, and investor-owned companies were granted specific, legally defined, and agreed-upon areas they serve. Co-ops serve about 400,000 homes and businesses in areas within 77 of Ohio’s 88 counties.

Service territories remained unchanged in the 1990s despite the deregulation that allowed competing energy providers to supply electricity to consumers through energy choice; co-ops and municipalities were specifically exempted. The PUCO’s regulatory authority does not extend to either government-run municipalities or member-run cooperatives.

And while that history is nice, members like the Bania family are just happy the place they live happens to be served by a co-op. “When our power was out for a couple of days during that winter storm a while back, we would watch our neighbor go out at all hours to get people reconnected,” Emily says. “He kept checking on us because he knew it might be a while and wanted to make sure we were OK. I can’t imagine you get that with the bigger companies.”

Service territory FAQs

What is a service territory?

Electric certified territories (ECTs), often called “service areas” or “service territories,” are geographic regions where an electric company — which may be either an investor-owned utility or a rural electric cooperative — has the obligation and exclusive right to provide electric service. The Public Utilities Commission of Ohio is the authority regarding ECTs, and you can view the PUCO’s interactive map of ECTs here.

What’s the difference between my co-op and an investor-owned utility?

Investor-owned utilities are business organizations that are intended to be profitable. An electric cooperative is a not-for-profit, member-owned utility that provides electric service solely to its members. Each cooperative has its own unique set of bylaws and is governed by a board of directors elected from and by the members of the co-op. Nationally, more than 800 distribution cooperatives serve about 56% of the U.S. land area and more than 21.5 million homes, schools, businesses, and farms.

Why does the PUCO not regulate cooperatives?

The PUCO does not have jurisdiction over electric cooperatives and municipalities by the definitions of a “Public Utility” as defined in 4905.02 of the Ohio Revised Code, which states that an electric company that operates its utility not for profit, or that is owned and operated by any municipal corporation, is not included.