When automobiles were first being developed more than a century ago, they were as dangerous to start as they were to drive. You didn’t just turn a key in the ignition or press a button on the dashboard as we do today. Rather, early car and truck engines were started by turning a hand crank that, at times, could suddenly and violently reverse direction and “kick back,” resulting in a person suffering a broken arm — or worse.

When one man was actually killed in such an accident, Henry M. Leland, the head of Cadillac, was determined to put an electric self-starting device on his cars. When his engineers failed to come up with a self-starter small enough to be practical, Leland turned to Charles F. Kettering. Kettering and his new company, Delco, accomplished the task quickly and efficiently, and electric self-starters first appeared on Cadillacs in 1912.

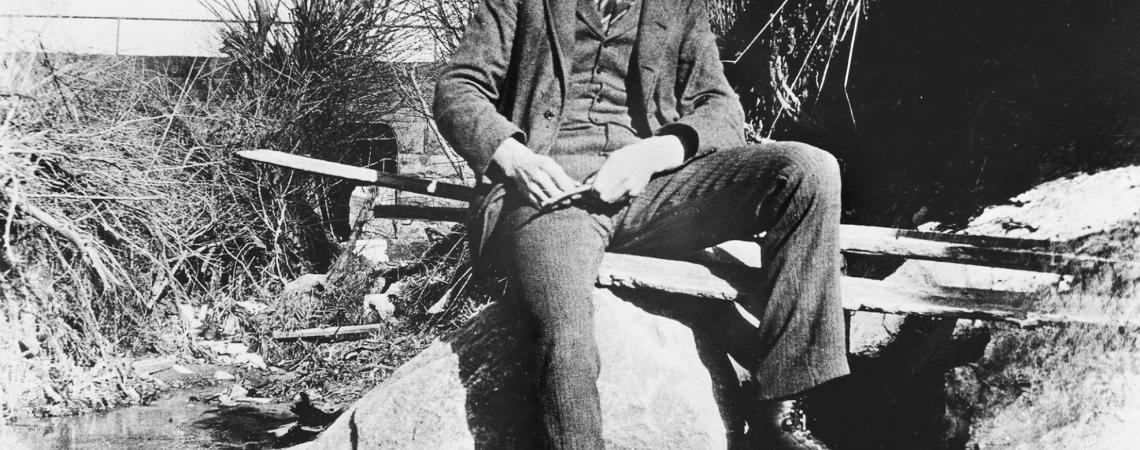

Charles F. Kettering working on his revolutionary electric car starter.

Born in Loudonville, Ohio, in 1876, Charles Kettering was the fourth of five children in his family. Poor eyesight caused him headaches in grade school, but he persevered to attend the College of Wooster before transferring to Ohio State University in Columbus. However, continuing eye problems eventually forced him to withdraw, and he took a job at the Star Telephone Company in Loudonville as foreman of a line crew.

Depressed at not being able to complete his education, Kettering applied his innate, unique thinking to his job. As a result, his spirits gradually revived. No doubt helping him recover mentally during those early years was meeting his future wife, Olive Williams of Ashland, Ohio. Eventually his eye condition improved enough that Kettering was able to return to college, graduating in 1904 from OSU with a degree in electrical engineering.

Kettering was hired out of college by National Cash Register (NCR) in Dayton to work in its research lab, where he distinguished himself as a practical inventor, securing 23 patents for the company in just five years. “I didn’t hang around much with the other inventors and the executive fellows,” he is famously quoted as saying. “I lived with the sales gang. They had some real notion of what people wanted.”

A colleague at NCR, Edward Deeds, eventually persuaded Kettering to partner with him and turn his talents toward the growing automotive industry. He and Deeds recruited other NCR engineers to join them nights and weekends tinkering in Deeds’ barn. The group became known as the “Barn Gang,” eventually incorporating as the Dayton Engineering Laboratories Company — better known as Delco — with Charles Kettering as its head. In 1916, Delco was sold to United Motors for $2.5 million — equivalent to about $60 million in today’s dollars — making Kettering and the other Delco founders a tremendous amount of money for the time.

From that point forward, Kettering’s professional career skyrocketed. He eventually acquired 186 patents, was the head of research at General Motors for 27 years, and was even featured on the cover of Time magazine on Jan. 9, 1933. One of Kettering’s co-workers at GM described him as “one of the gods of the automotive field, particularly from an inventive standpoint.”

Describing his perseverance, can-do attitude, and knack for invention, Kettering is quoted as saying, “People won’t ever remember how many failures you’ve had, but they will remember how well it worked the last time you tried it.”

Yet for all his wealth and national fame, Charles Kettering never forgot his small-town roots, returning to Loudonville occasionally to visit family and friends. In August 1946, on his 70th birthday, the town threw an elaborate celebration for Kettering, and he brought along with him a fellow inventor who happened to also live and work in Dayton: Orville Wright. Yes, that Orville Wright, half of the famous Wright brothers team who had invented and flown the world’s first airplane in 1903.

Various schools and colleges are named for Kettering, as is the Dayton, Ohio, suburb. His many philanthropic works include financing the building of Kettering Hospital in Loudonville in 1957. Today, he is remembered through the eight Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center locations in New York City. In southwest Ohio, the Kettering Health Network includes nine hospitals and medical-center campuses.

Charles F. Kettering died in 1958 at the age of 82. Yet after all the ensuing years, at least two Kettering scholarships are still presented annually to graduating Loudonville High School students. One scholarship is awarded in the field of agriculture; the other, not surprisingly, for science and technology.