Is there really a Lake Erie monster, as some claim? Well, yes, at least potentially. In fact, thousands of small ones are swimming in the big lake right now. Let me explain.

In the early 1800s, untold numbers of lake sturgeon weighing hundreds of pounds each and measuring up to 6 feet or more in length roamed the Great Lakes. One of North America’s largest freshwater fish, sturgeon initially had little economic or food value to humans. Additionally, the fish were highly destructive when unintentionally caught in commercial fishing nets set for more desirable species. As a result, lake sturgeon numbering in the thousands were simply dragged up on beaches to die and rot or were fed to hogs.

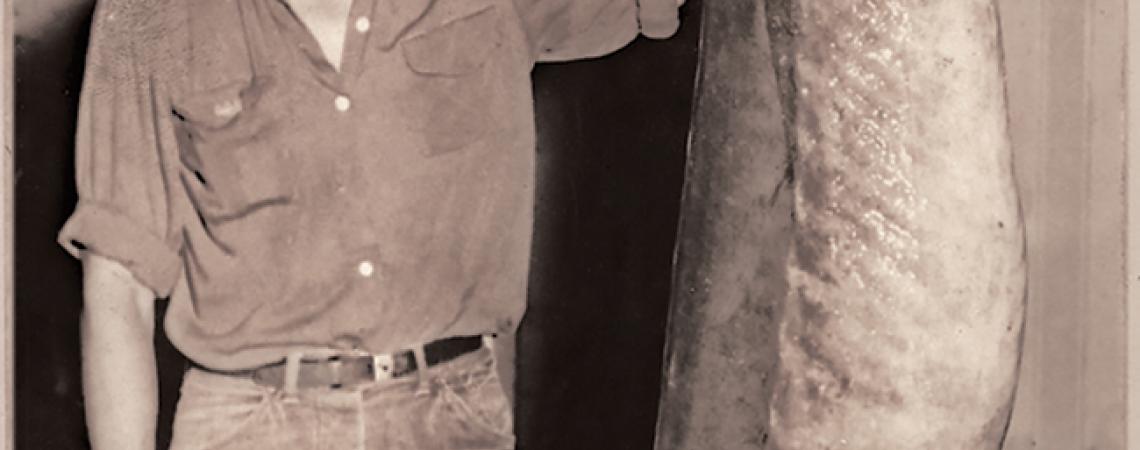

Historic photo, Lake Erie lake sturgeon. (Photo courtesy of Ohio Division of Wildlife.)

By mid-century, however, market conditions were rapidly changing, and from 1850 to 1870, products derived from sturgeon transformed this once-worthless fish into a valuable commodity. Caviar, fish oil, and a substance known as isinglass — a gelatin used in adhesives made from the air bladder of various fish, especially sturgeon — became extremely valuable. The fish became so sought after, in fact, that one of the largest sturgeon fisheries in America developed on Lake Erie. In 1885 alone, commercial fishermen on Erie netted more than half a million pounds of lake sturgeon.

But little did anyone at the time realize the party was about over. During the following two decades, the sturgeon fishery collapsed on both the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River. A double threat took the big fish down: unregulated fishing, combined with the damming of tributary rivers that eliminated essential spawning habitat.

Also contributing to the population crash was the extremely slow reproductive rate of sturgeon. Although lake sturgeon are believed to have a lifespan similar to humans, females do not become sexually mature until 20 to 25 years of age, then spawn only once every four to six years. Males take 15 years to mature, spawning every one to four years.

A long-term program to reintroduce lake sturgeon to Lake Erie is currently underway on the lower Maumee River near Toledo. The Toledo Zoo is spearheading the effort, aided by state, federal, and provincial government agencies, as well as several universities. The young fish are raised for six months in a special streamside rearing facility that circulates Maumee River water through its holding tanks. The idea is to imprint the 7-inch sturgeon with a chemical signature that will help them find their way home from Lake Erie in coming years.

“With continued annual fall stockings of about 3,000 sturgeon fingerlings that began three years ago, our hope is that this gentle giant of the Great Lakes will eventually begin spawning again in the Maumee and other Lake Erie tributaries, establishing a self-sustaining population,” says Matt Cross, conservation biologist for the zoo.

According to the Division of Wildlife, last fall a commercial fisherman in the Western Basin of Lake Erie caught a sturgeon identified as one of the fish released a year earlier. It’s the first instance of one of the sturgeon from the reintroduction program being recaptured — a positive sign that the project is on the right track.

W.H. “Chip” Gross is Ohio Cooperative Living’s outdoors editor.