Looking like a miniature army helmet with legs, box turtles are unique in that they are the most terrestrial of Ohio’s nearly one dozen turtle species. They get their name from the fact that they can literally “box themselves in” from predators, doing so by closing a hinged flap on their bottom shell tightly against their top shell.

Consequently, a raccoon, possum, fox, skunk, or coyote may roll a box turtle around for a few minutes trying to figure out the puzzle, but the turtles are used to that. Once the predator gives up in frustration and moves on, life resumes its typical leisurely pace for the docile box turtle.

The box turtle is the most terrestrial of Ohio’s nearly one dozen turtle species.

Alan Walter of Carrollton has extensively studied the box turtles living on his property in eastern Ohio. Walter owns a 150-acre tree farm in Harrison County that he manages for timber and wildlife, so he has spent countless hours in the woods over the past 30 years.

“During that time, I have found and photographed a total of 63 box turtles, seven of which were young ones,” Walter says. “Five of the adults I have found a second time — one 19 years later. From the place where I first discovered it, that particular turtle had moved about 1,000 feet. By contrast, another turtle I found 16 years later was only 50 feet from where it was first spotted.”

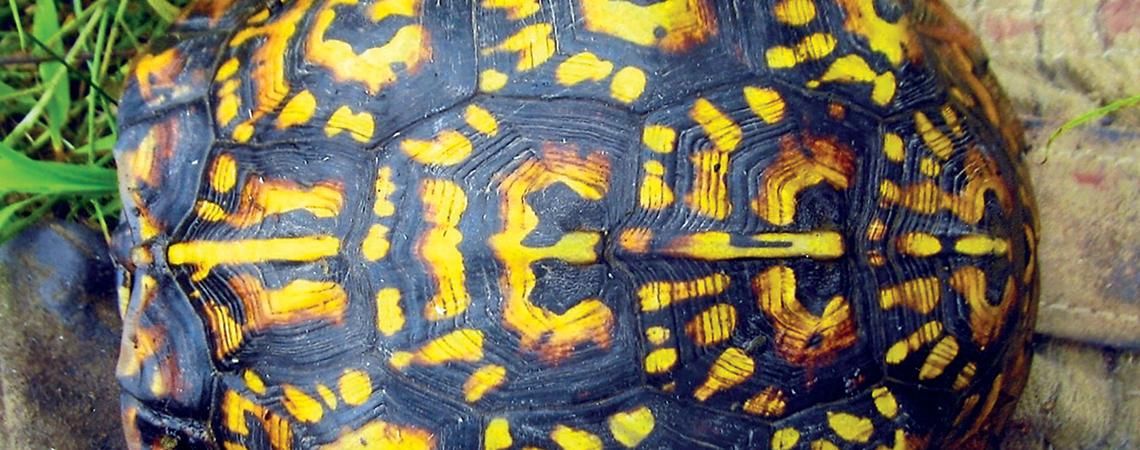

Walter knows whether or not it’s the same turtle by the natural markings on the turtle’s shell. Whereas some people mark box turtles with dabs of paint to recognize them again, Walter takes their picture. “Each box turtle’s top shell — known as a carapace — is uniquely marked,” Walter says. “So all I have to do is compare a turtle I find with my previous photos to know if I’ve located the same one or a new one,” he says.

Greg Lipps, a member of Tricounty Rural Electric Cooperative, is amphibian and reptile conservation coordinator at Ohio State University. He says that box turtles typically have a home range of about 70 acres and are relatively long-lived, compared to other wildlife.

“We know they can live a century or more,” says Lipps, “but 40 to 50 years is more the typical life span.”

Historically, box turtles were found statewide, except for two areas. They were not in the extensive region of the Great Black Swamp in northwest Ohio because box turtles are mainly a terrestrial species, and they also were not found in northeast Ohio. At least one well-respected turtle researcher believes that’s because there were large Native American settlements in that region for centuries.

Lipps says that Indians not only ate box turtles but that some tribes even buried them with their dead — up to a dozen or more turtles per grave.

Was the act simply ceremonial, or were the turtles intended to be food for the deceased during their journey to the afterlife?

“No one knows for sure, but the entire theory is a really fascinating concept,” Lipps says. “The good news today is that the so-called ‘hole’ in the population in northeast Ohio is gradually filling in. Overall, the population in Ohio seems to be holding its own, doing as well as can be expected given the amount of available habitat.”

Next to habitat loss, likely the biggest threat to box turtles is from motor vehicles. If you happen to see a box turtle on a roadway — and you can safely pull your vehicle off the road — you can move the turtle to the side of the road in which it’s headed. If you put it back on the side of the road where it came from, the turtle will only try crossing again.

W.H. “Chip” Gross is Ohio Cooperative Living’s outdoors editor and a member of Consolidated Cooperative.