Since electric co-ops were first established during the 1930s, they have served mainly rural areas of the United States. As the decades passed and the country’s geographic distribution of population changed, some electric co-ops whose membership was once entirely rural now count more densely populated areas — suburbs, or even nearly urban areas in some cases — as parts of their service territories.

The demographic shift brings changes, including new members who are joining an electric co-op for the first time — many of whom have never previously even heard of co-ops.

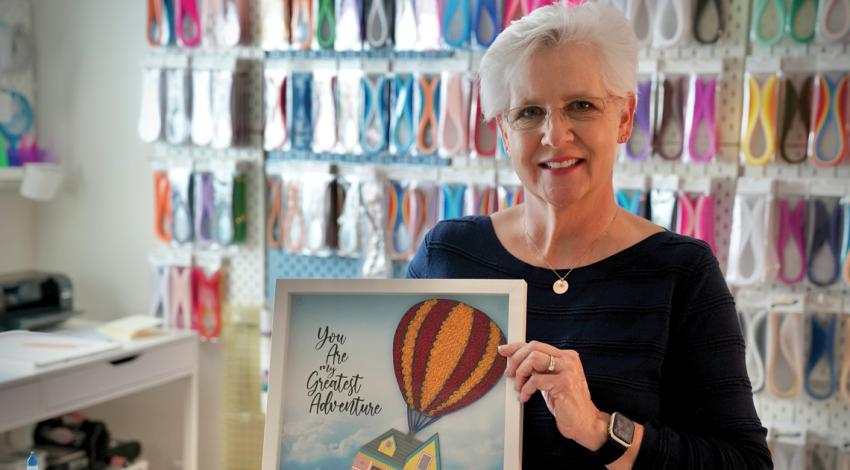

Suburban Columbus’ growth is bringing changes to the electric co-ops that serve it. (Photo by Mike Cairns.)

“We continually beat the drum among our members about what the co-op is,” says Phil Caskey, president and CEO of Consolidated Cooperative, which serves eight counties in north-central Ohio. Caskey says that many residents of suburban areas, as well as former suburbanites who move into rural areas, are unaware of the differences between electric co-ops and large, privately owned electric utilities. In addition, rural co-op members tend to have a better understanding of the co-op’s place in the community, he says.

Cindy Brehmer, for example, experienced the service-first business model of electric co-ops for the first time when she moved from Illinois to Pickerington, Ohio, in 1999 and became a member of South Central Power Company. One day, the electricity suddenly switched off in the home she shares with her partner, Doug Baden. “I thought it was a breaker,” she says, “because when I went to other parts of the house, the power was on.” After checking the breaker box and finding nothing amiss, Brehmer and Baden called the co-op, which serves 24 counties across wide areas of southern and eastern Ohio — including much of Fairfield County.

The technician who investigated the unusual problem discovered that part of the buried electrical line to the 1970s-era home had rotted away. “He had it fixed within 24 hours,” Brehmer says. The co-op has helped her family in other ways, too. Baden’s health suffers if the electricity is out and he cannot use the CPAP machine that keeps him breathing at night. Since they alerted the co-op and filled out a medical need form, Brehmer says, “the longest we’ve ever had our power out was two hours.”

Even as recently as 1999, large areas of Fairfield County were sparsely populated farmland. Since then, however, once-tiny villages such as Pickerington and Canal Winchester have seen exponential growth, and Rick Lemonds, president and CEO of South Central Power Company, says the co-op has made changes designed to improve communications with members, including newer and younger members who have only recently become part of the co-op’s demographic.

“Up until three years ago,” he says, “our primary means of face-to-face communication with members was our annual meeting.” However, that meeting was always held in the same location — and on a weekday — so many members couldn’t attend because they were at work. Now, Lemonds says, the co-op is “bringing the meetings to members” by holding district meetings in different locations at night, complete with barbecue dinners and entertainment. Meeting attendance has increased by 30%, he says. “A lot of people were very appreciative. We’re encouraged by that.”

Union Rural Electric Cooperative, which serves suburban areas just outside of Marysville city limits, as well as extremely rural areas elsewhere in Union County, is another co-op that has made changes to account for an increased number of non-rural members. When the membership was mostly rural, says President and CEO Anthony Smith, members often visited the co-op’s main office to pay bills and attend to other business. Now, he says, “We don’t get as much walk-in traffic as we used to. Everyone wants to do business online.” So, members can now pay their bills on the co-op’s website.

Caskey, Lemonds, and Smith agree that the rural and suburban members of their territories have somewhat different needs and expectations. Rural members are more accepting of aboveground lines, the managers say, and they understand that storms sometimes lead to power outages that are difficult to restore. Suburban members, on the other hand, usually prefer buried lines — often for aesthetic reasons — and they have lower tolerance for those inevitable outages.

To accommodate the needs of both the rural and suburban areas of their service territories, Consolidated Cooperative, South Central Power Company, and Union Rural Electric Cooperative all have robust websites and a strong social media presence, which they use to communicate with members. In addition, all three co-ops have made it possible for members to pay their bills through apps on their smartphones. In early 2019, South Central Power Company released its own dedicated app for members’ use. “We converted our entire billing system,” Lemonds says, “so our members will be able to use technology to do business with the co-op.”

Brehmer, for one, is grateful for the efforts her co-op makes to serve its members. “They are always nice and always helpful,” she says. “I like to give credit where credit’s due.”