Tucked off County Road 658 in Ashland County, not far from the northward-flowing Vermillion River, a squat, knobby tree stump sits near a modest white farmhouse.

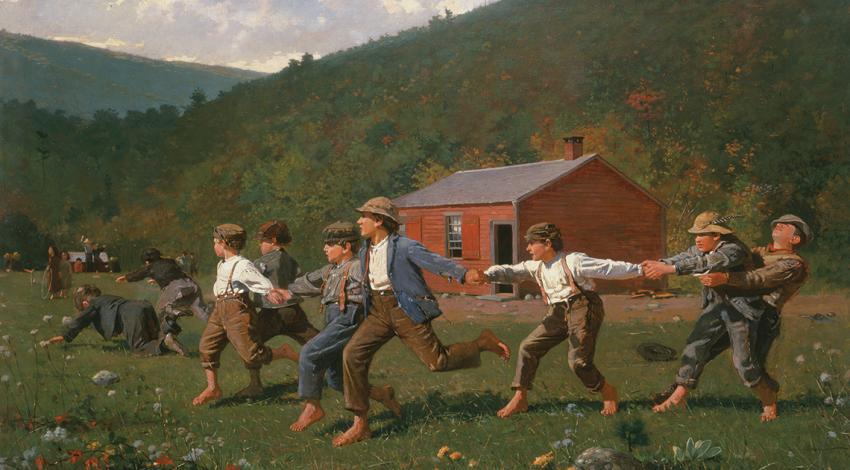

Folklore paints Johnny Appleseed as an eccentric nature lover, scattering apple seeds while wandering barefoot and wearing a tin pot as a hat. While he was a devout conservationist, he was also a calculating and successful orchardist whose passion sprang from a blend of religious devotion, humanitarianism, and strategic economic thought.