On a splendid day in May when bright sunshine bathes Ohio and seems to portend progress against the coronavirus, Missy Duer arranges bottles of whiskey in the antique-laden tasting room at Indian Creek Distillery. She’s explaining why Elias Staley’s signature graces bottles of their straight-from-the-still white rye when her husband, Joe, pops in with a question.

“We got an order for 400 more hand sanitizers,” he says. “Should we use those new labels you designed?” Nodding, Missy replies, “Yes, and we’d better print them ASAP.”

The Duers are Pioneer Electric Cooperative members who live on Staley Mill Farm, where, in 1818, Elias Staley and his two brothers built a gristmill in the wilderness along Miami County’s Indian Creek. Elias, who was Missy’s maternal great-great-great-grandfather, subsequently purchased the farmstead and, in 1820, constructed a distillery that produced double-distilled Staley Rye whiskey. During the Civil War, Elias shuttered the distillery to protest a federal alcohol tax, but after he died in 1866, his sons reopened the stills. Staley descendants continued making whiskey until Prohibition put them out of business. Missy’s great-grandfather, George Washington Staley, foiled government revenuers by hiding Elias’ copper pot stills and distilling equipment inside the farm’s whiskey warehouse. Following her mother’s death in 2007, Missy inherited the farm, and she and Joe moved into the Federal-style farmhouse Elias erected in 1825.

Indian Creek Distillery produces about 5,000 bottles of artisan rye and bourbon per year, using grains grown in Darke County.

“This farm has always been the hub of my family’s life,” says Missy. “I grew up two minutes away and loved coming here as a girl. Now my grandchildren represent the farm’s eighth generation of Staleys, and they love it, too.”

Although Elias’ distillery fell into ruin, most of the structures comprising his frontier-era agricultural and industrial complex — including the gristmill and an 1820 sawmill — still exist. “The gristmill is Ohio’s oldest originally standing mill,” Missy says. “It has two 11-foot waterwheels and looks as if the Staley boys just put down their hammers and walked away.”

While sorting through two centuries’ worth of family letters, ledgers, furnishings, farm implements, whiskey jugs, and tools, the Duers had an “aha!” moment that prompted them to resurrect Staley Rye. “We realized that we could again make Elias’ whiskey on the farm because George Washington Staley had saved his old stills and his recipe,” says Missy.

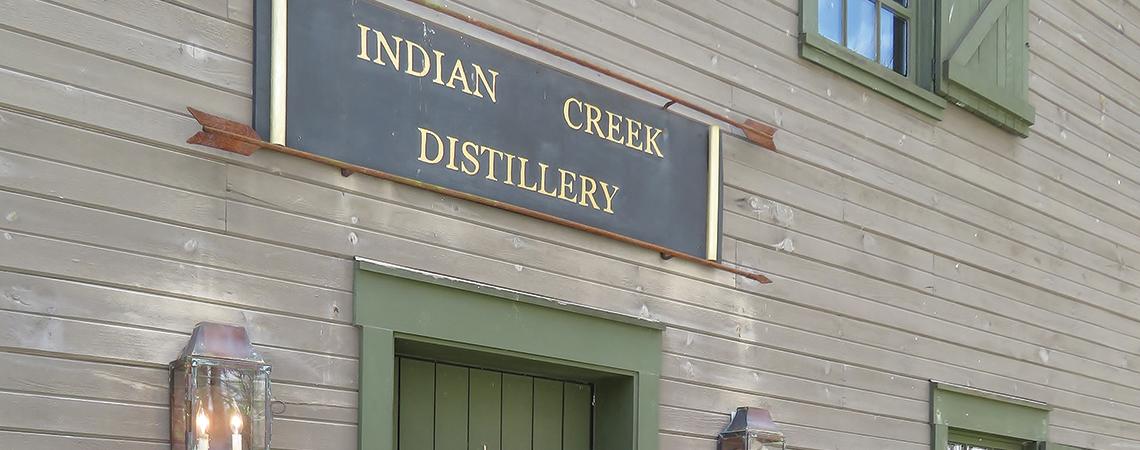

While neither she nor Joe had distilling experience, they’re a can-do couple whose ventures have ranged from farming and construction to jewelry-making and a health food store. They hired Amish builders to construct a new stillhouse with simple, rustic-looking architecture that blends seamlessly with the farm’s historic buildings. “When I heard the Amish crew speaking Low German among themselves, it felt like Elias was saying ‘ja’ to our new distillery,” recalls Missy. “Since he was raised in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, they were talking his language.”

Today, Indian Creek Distillery produces about 5,000 bottles of artisan rye and bourbon per year, using grains grown in Darke County. “It’s an extremely small-batch distillery,” says Missy. “We use a slow, old-fashioned process that takes a long time to produce what we feel is authentic frontier whiskey.” Thanks to Elias’ venerable pot stills, the Duers also claim to operate America’s oldest working stills. “Nobody else has original stills and documentation like we do,” Missy says.

Elias never could have imagined hand sanitizer being made at a distillery on his farmstead. Yet from the time he produced the flour and whiskey that sustained early America to modern day, when the coronavirus is a fact of life, the Staleys have contributed a strong entrepreneurial thread to the fabric of the nation. For the Duers, Indian Creek Distillery is a way to perpetuate that legacy by naming products like Andy’s Old No. 5 Bourbon after an ancestor who made whiskey all his life and by introducing customers to the pioneer spirit through farm tours and whiskey tastings.

“It’s such a blessing to carry forth an inheritance like this farm and the distillery,” says Missy, “and we feel a responsibility to do it passionately, thoughtfully, and well.”