Ohio is known for producing more United States presidents than any other state in the Union — eight in all, including several who were veterans of the Civil War. First among the veterans, and perhaps appropriately so, was General Ulysses S. Grant.

Grant had the benefit of education as a boy, as his parents were of apparent means to pay for schooling. Grant attended private schools in Georgetown, as well as the Maysville Seminary across the river in Kentucky. In his late teens, he attended a school operated by the Presbyterian minister John Rankin in Ripley, Ohio. Rankin is perhaps best known as an ardent and outspoken abolitionist. He was perhaps the most significant conductor of freedom-seeking slaves on the Underground Railroad. It’s no great intellectual leap to think that Rankin’s ethos toward individual liberty affected the future warrior-president.

He was born Hiram Ulysses Grant two centuries ago this month along the Ohio River where it starts to make its serious bend to the north toward Cincinnati in Clermont County. It was April 1822 — not too far removed from the frontier period. His parents, Jesse and Hannah Simpson Grant, had made a home in Point Pleasant, Ohio, a year earlier, and in fact, just a few years after the tiny river town was platted.

Grant descended on his father’s side from a family long-established in America, dating to the Massachusetts Bay Colony circa 1630. His great-grandfather served the British in the French and Indian War, and his grandfather aided the colonists’ cause at the famed American victory at Bunker Hill in the American Revolution. Perhaps, then, it was no surprise that the 5-foot, 2-inch 17-year-old Grant would accept an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, in 1839.

His father, Jesse, a tanner by trade, was an avowed abolitionist Whig — as were many southern Ohioans at the time. He petitioned Congressman Thomas Hamer, a Georgetown, Ohio, schoolteacher, lawyer, and former speaker of the Ohio House of Representatives, for his son’s appointment to the military academy. Hamer obliged.

The irony is palpable: Hamer was a pro-slavery Jacksonian Democrat. And there’s this: Hamer did not know the Grant family well, and his recommendation for the teenager erroneously named him “Ulysses S. Grant,” assuming the young man took his mother’s maiden name as a middle name. The congressman’s mistake in nomenclature turned Hiram in to “U.S.,” which became his nickname at the academy — short also for “Uncle Sam,” which also explains why friends and close associates also called him “Sam.”

Grant completed his studies at West Point in 1843, by then having grown another 5 inches. The 5-foot, 7-inch second lieutenant landed at Jefferson Barracks, Missouri, where he served in the infantry (despite his demonstrable horsemanship) and also met and married a Missourian, Julia Dent.

Jefferson Barracks was commanded by General Stephen Kearney and would serve as the launching point from where the U.S. Army would invade Mexico in 1846 and take over much of today’s American Southwest. Grant, serving in a regiment of regulars, served with great distinction, but the affair left him questioning the legitimacy of vanquishing an easily conquered foe and examining his own conscience in the matter.

In 1854, following bouts with drunkenness, he resigned his Army commission and returned to civilian and family life in Missouri. By turns he failed at several endeavors: farming, tannery, firewood sales, and real estate speculations. When the Civil War began, he accepted a commission as a U.S. Army colonel to lead a regiment of Illinois volunteers. His experience in Mexico served the Union cause well, as he understood that victories are made in supply lines away from the tactical battlefield.

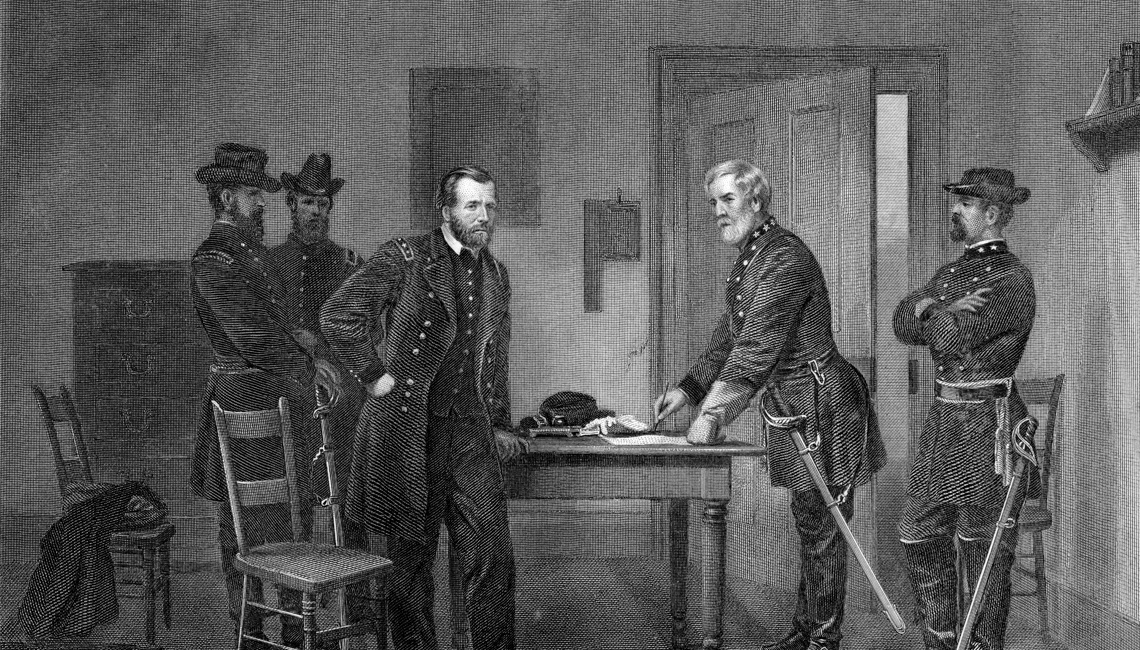

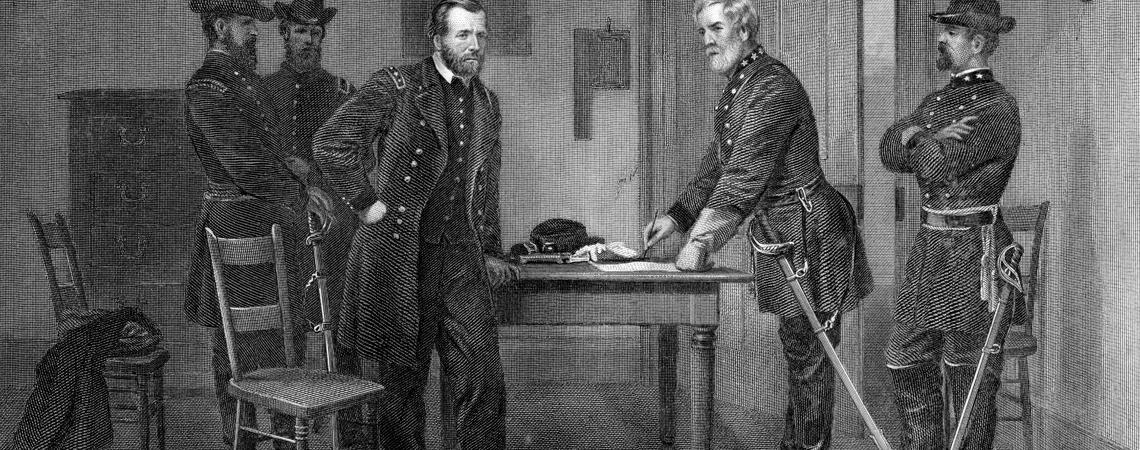

Grant’s successes in the South were legion, and that convinced Lincoln to have Grant lead the whole affair and draw the horrible war to a close. Grant vanquished Lee at Appomattox Courthouse, and there signed the terms of the South’s surrender.

His popularity soared, and he ascended to the presidency in 1869. He would sign into law Reconstruction and Civil Service acts, macerate the Klan, champion the 15th Amendment, create the U.S. Fish Commission, and establish our first national park, Yellowstone.

Along with Grant’s bicentennial birthday, this year also marks the sesquicentennial of his 1872 reelection. Grant, a Radical Republican, was challenged in the primary by Ohioan Salmon P. Chase, who holds the distinction of having served in Congress, in a presidential cabinet, and on the U.S. Supreme Court. The Democrats did not put up a candidate, and instead endorsed Horace Greeley, from a splinter group called the Liberal Republicans, who was selected at that group’s convention in Cincinnati in May of that year. Grant vanquished Greeley in November.

Grant had another nickname from his initials and from his war exploits: “Unconditional Surrender.” But he surrendered to throat cancer in 1885 at the age of 63. Fortunately for us, the Union survived because of a tenacious patriotic Ohioan shaped by his youth along the north-flowing bend in the river.