Shawana Mitchell and her fiancé, Joe Hedges, were regulars at Circleville’s VFW lodge poker nights, and, as they often did, joined the card-playing crowd one Friday evening in March 2021 with their friend Troy Fletcher.

They were having fun, joking and trash-talking, when suddenly Joe stood up, telling Troy that his chest hurt.

Joe went to Shawana and told her. Thinking “heart attack,” Shawana urged Joe to sit down and headed to the bar for aspirin. Joe started to follow her through the doors that led to the bar, and Troy, seeing Joe begin to fall, caught him in his arms.

Joe said something Troy couldn’t understand. His lips were blue.

Troy Fletcher acknowledges a sense of survivor’s guilt after he received his friend Joe Hedges’ kidney when Joe died in March 2021.

The emergency squad arrived, and Joe was taken to Circleville’s Berger Hospital, then flown to Riverside Methodist in Columbus for emergency surgery.

Joe, 52, had suffered an aortic dissection, a tear in the inner layer of the body’s main artery. When Shawana saw him after surgery, his color had improved and she dared to hope. But brain swelling ensued, and Sunday morning, Joe’s family was called to the hospital.

As they got the devastating news, they were introduced to a representative from Lifeline of Ohio, an independent nonprofit organization that promotes and coordinates organ donations in the state. After hearing about the widespread need, Shawana and the family decided Joe would become an organ donor.

As they got the devastating news, they were introduced to a representative from Lifeline of Ohio, an independent nonprofit organization that promotes and coordinates organ donations in the state. After hearing about the widespread need, Shawana and the family decided Joe would become an organ donor.

That need, it turned out, was closer than they knew. Unbeknownst to them, Troy was on a waiting list for

a kidney transplant. When they found out, the family decided immediately to donate Joe’s kidney to Troy.

Of course, it’s not that simple, says Jessica Peterson, supervisor of media and public relations at Lifeline of Ohio. Donors and recipients must have compatible blood and tissue, just for starters, and for a selected organ recipient to match the donor is extremely rare. In Peterson’s nine years at Lifeline, she says she knew of only one successful directed donation.

But Joe and Troy were a perfect match. Four days after Joe collapsed, Troy was at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center to receive his friend’s kidney.

This month, March 2023, is the anniversary of Joe’s sudden death and Troy’s gift of life. Troy, now 40, remains on a waiting list for a pancreas, but he’s feeling healthy and well. “I’ve not had a lick of trouble,” he says. Before receiving Joe’s kidney, Troy says, “I was ready to die. It’s changed my life drastically. I knew God had a plan, and now I really know.”

Troy acknowledges some survivor’s guilt. His friend died, while he’s enjoying better health. In gratitude, Troy said, he and Shawana, 42, are registered organ donors, though Troy laughs about his donation prospects. “If someone wants these terrible eyes, they can have them,” he says.

And there’s a happier end to the story as well. The shared grief over Joe’s death, the several interviews Shawana and Troy have given together, and Troy’s determination to take care of Shawana pulled them together and resulted in another gift: Shawana and Troy are a couple now. “My goal,” he says, “was to make sure she was laughing every day.”

Chris Wasielewski of Delaware County, Ohio, was driving his son, Adam, 6, to school on May 4, 2010, when their car collided with a dump truck. Both were hospitalized; Adam died of his injuries a month later.

The family was struggling with the unimaginable when a Lifeline of Ohio family service coordinator approached the Wasielewskis about donating Adam’s organs.

“Chris and I were registered organ donors at the time of the accident,” Marcia Wasielewski wrote in an email. “We never discussed what that would look like for our children in this situation.”

Jessica Peterson, Lifeline’s spokesperson, said the initial contact with a potential donor family is undertaken with all the sensitivity and care it deserves.

“It’s literally the worst time,” Peterson says. “That’s how donation happens. It happens in the most tragic of circumstances.”

Because the Wasielewskis agreed, Adam’s corneas and heart valves now are giving their recipients better lives.

Marcia Wasielewski said she and her husband do not know who received Adam’s donations, but they have “adopted” other organ recipients as their own.

Adam’s is among the many names engraved on Lifeline’s Donor Memorial at Lifeline of Ohio’s building in Columbus. Nearby is a photograph of Adam as a kindergartner, grinning next to his elementary school sign. The sign’s message reads, “Class of 2022.”

Lifeline’s memorial is unique in Ohio, Peterson says. The state has three other organ donation centers: Life Connection of Ohio, in Dayton and Toledo, serving northwest and west-central Ohio; Lifebanc in Cleveland, serving northeast Ohio; and LifeCenter in Cincinnati, serving southwestern Ohio and parts of Indiana and Kentucky. The building at 770 Kinnear Road serves central and southeast Ohio. It is the only one with land that accommodates a memorial.

The Wasielewskis remain active Lifeline volunteers.

“I am very passionate about speaking on behalf of Lifeline,” Marcia Wasielewski wrote. “I am always happy to talk about Adam.”

Peterson says the dedication that Lifeline’s many loyal volunteers bring to the organization enhances its mission to save and heal lives through the gift of donation.

“Once they’re with us, they’re with us,” she says. The memorial, designed by Rogers Krajnak Architects, suggests the “ripple effect” that one donor can have on dozens of lives.

Lifeline’s many volunteer-driven programs honor donors and recipients, including the annual 5K Dash for Donation; Shawls of Support, knitted by Lifeline donors, recipients, and community members and given to donor families; and commemorative quilts, whose squares are provided by donor families and pieced by volunteers.

Every Monday, Lifeline staff members gather in the lobby, near a wall on which a tree is painted. As the names of that week’s donors are read aloud, an associate places a leaf on the tree. The leaf’s size indicates the type of donation: organ, eye, or tissue. Smaller leaves represent children.

“We say their names,” Peterson says. “I work with the most compassionate people around.”

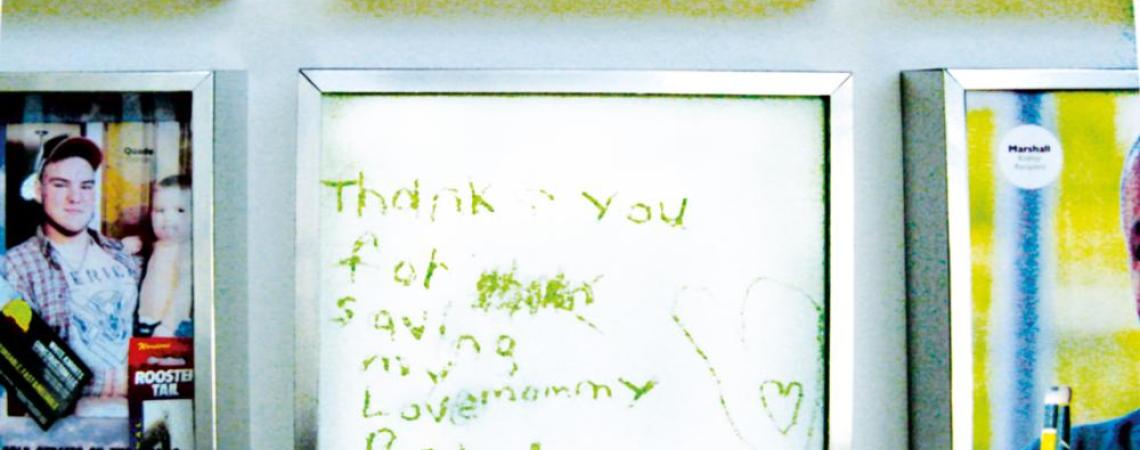

In Lifeline’s atrium, shadowboxes honor both organ donors and recipients. Families provide the photographs, mementos, and other keepsakes. The boxes are displayed for a year, and photographs remain on Lifeline’s website after the boxes are returned to their families.

“These are cherished, cherished things,” Peterson says.

Sixty percent of Ohio residents are registered organ donors, more than the national percentage of 50. Peterson credits the Ohio Bureau of Motor Vehicles, whose employees ask drivers about organ donation, with helping to spread the message.

However, the vast majority of Ohio’s residents never end up donating organs. A person must die in a hospital, on a ventilator, to be eligible. Only 1% of registered donors meets this requirement.

According to Lifeline, a single person may donate a total of eight organs: the heart, two kidneys, two lungs, the liver, the pancreas, and the small intestine. Eyes and tissue also may be donated.

Donors rarely give all eight. Every donated organ must be viable and healthy, Peterson says. The occasions when it happens, she says, are “very, very special.”

When an unregistered adult or a child dies in the hospital on a ventilator, a Lifeline family services coordinator asks the family about donation. Lifeline associates never look away from the naked pain these families are facing.

“We wrap our arms around them as tightly as we can,” Peterson says.