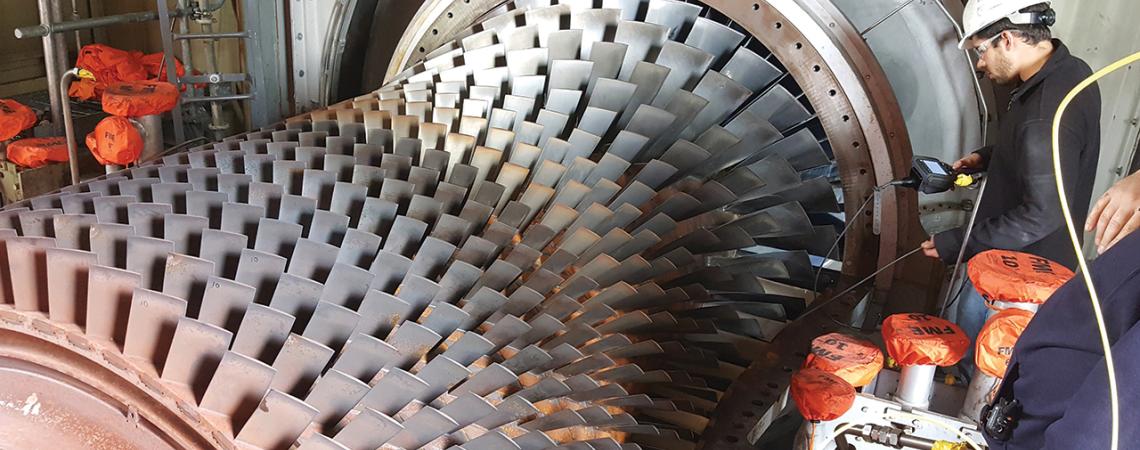

Nick Mascia, project engineer at Buckeye Power, uses a borescope to look for damage to a turbine at the Mone plant.

During the year’s milder periods, a peaking facility like the Greenville Generating Station might go six weeks without spinning up to produce electricity for Ohio electric cooperative consumer-members.

However, when extreme heat or a disaster strikes, the plant answers the call. For example, when tornadoes caused devastation around Celina last Memorial Day, Greenville was online around the clock for the next three days.

The really interesting part? For either extreme, it’s up to a crew of only four to make sure the power stays on.

“That’s kind of our M.O.: When those really hot or really cold days hit, when emergencies happen, any time the grid is having issues, we’re here to pick up the slack and stabilize things,” says Dave Richardson, plant manager principal. Richardson oversees operations at the Greenville plant in Darke County, along with the Robert P. Mone Plant, located about an hour away in Van Wert County.

Both facilities, fired by natural gas, are “peaking plants,” meaning that they are only brought online when the power grid is stretched to its limit. Those dog days of summer, when the AC’s on high in seemingly every household and business, or in the heart of winter is when facilities like Greenville typically see the most run time.

“Ninety percent of the time, we’re like the fire department, in that we’re on call for when we’re needed,” Richardson says. “We can be on the grid in less than 30 minutes. During a hot stretch, like [June] through September, typically we’ll run 15 to 20 days a month, but not necessarily for long starts. The runs can be an hour or can be what happened during the storm — 75 hours straight.”

The Greenville plant contains four turbines, each with a nominal capacity of 50 megawatts (MW). All are capable of operating in synchronous condensing mode, allowing the turbine to supply or absorb reactive power. Richardson says the station is typically online between 500 and 1,200 hours a year. The Mone plant has three turbines rated for 175 MW each.

“These turbines are really fast — they’re essentially jet engines, just like what you’d see hanging from the wing of a plane,” says Andy Williams, Greenville Station’s energy production supervisor. “We keep them in top condition so that they’re ready to start at any moment. Every morning, we go through and check the system, so that when the call comes to start them up, it’s literally only minutes until we have them online.”

Keeping facilities like Greenville and Mone ready to run at a moment’s notice, or bringing them back online after repairs that are invariably needed, requires technicians comfortable with a variety of responsibilities. With only four people assigned to the stations, each person there must be ready to address electrical, mechanical, or computer issues at any moment. Self-reliance, dependability, creativity, and strong communication skills are all critical to maintaining and operating stations like Greenville and Mone, says Mike Yorkovich, energy production supervisor at the Mone plant.

“We wear a lot of different hats,” Yorkovich says. “Keeping communications open among the crew is essential, so that you know what’s been worked on and what hasn’t. Sometimes you have to come in on a Thanksgiving afternoon — that’s just how it is. These guys are all very dedicated and proud of this place, like a home away from home. We’re essentially a family — everyone knows each other’s kids and wives, when their graduations or ballgames are coming up, all of that.”

When something significant does go wrong, it’s that sense of teamwork and creativity that’s needed to get back online quickly. For example, last year at the Mone plant, the crew discovered that the tip of a rotor blade had broken loose inside a turbine, causing significant damage within. But once the crew got the casing off, they discovered that a number of damaged vanes were wedged in place, making it impossible to finish the repair. At that point, it looked like they would have to pull out the entire rotor and ship it to South Carolina for repairs. “That night, our guys sat around the office trying to come up with a solution,” Yorkovich says. “Before long, Kevin Fletcher says, ‘Why don’t we just try a post driver?'”

Using the simple farm tool, the vanes were freed in a matter of minutes and repairs could continue. “That small idea saved us, I’d say conservatively, at least a million dollars, and got the unit back online 30 to 60 days faster than it would have otherwise,” Richardson says. “That’s the kind of people we have working at these stations.”