When Dewey Scott retired from the hustle and bustle of Cincinnati to the peaceful hillsides surrounding Ripley — an hour to the southeast on land hugging the Ohio River — he thought he’d enjoy life without much on his to-do list.

“My wife, though, told me I needed a hobby,” he says. “So, I went down by the river to read, opened up the newspaper, and saw the John Parker House needed a tour guide. I walked across the street and applied for the job.”

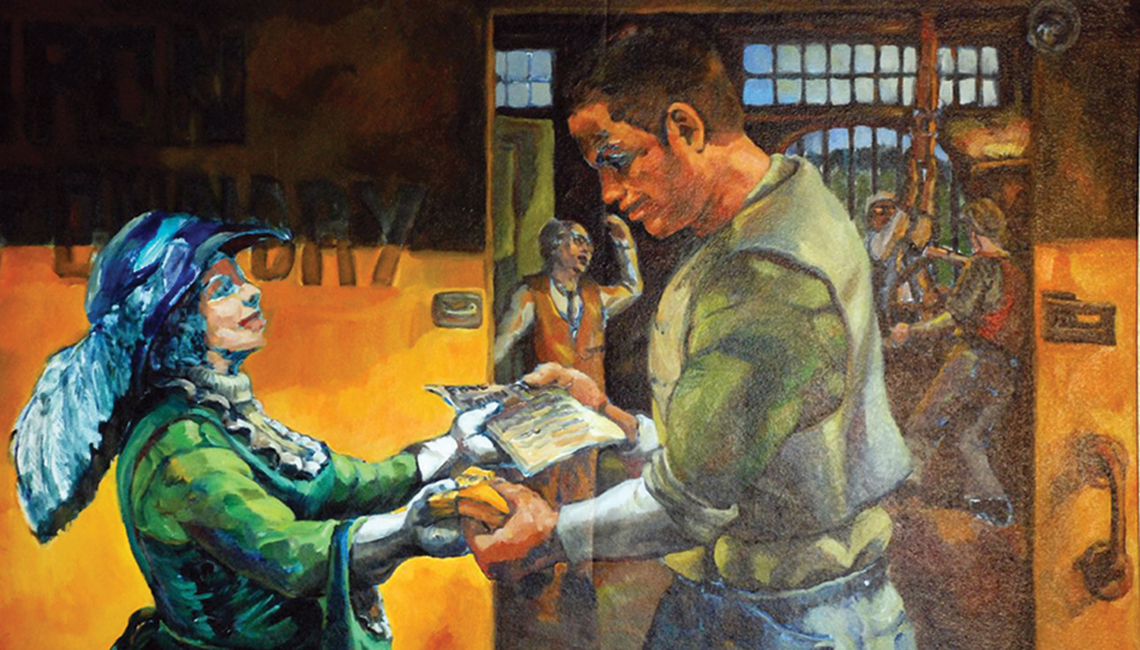

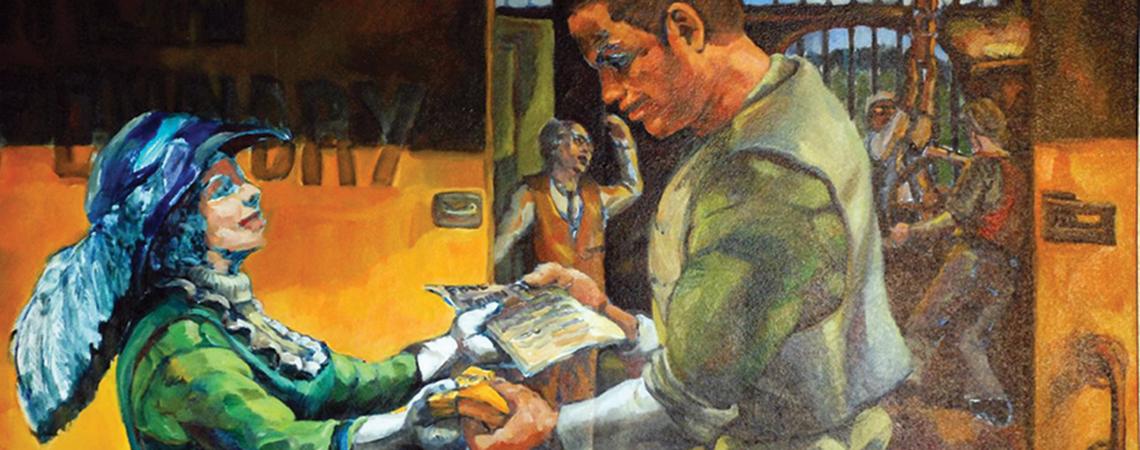

A piece of artwork at the John Parker House museum in Ripley depicts travelers and “conductors” on the Underground Railroad.

That was more than a decade ago. Today, Scott is the manager and docent at the John Parker House museum in Ripley, armed with a knack for storytelling and a wealth of knowledge about the historic home and about Ripley’s standing as a pivotal stop on the Underground Railroad.

“You were a free person once you came into Ohio at that time,” he says. “It was known that there were free blacks living in Ripley, and fugitive slaves knew they could come here and live among them.”

Ohio’s location was key. “If you look at a map, you’ll see Ohio is the southernmost free state that bordered the northernmost slave states of Kentucky and (then) Virginia,” says Eric Herschthal, postdoctoral fellow in the Department of African American and African Studies at Ohio State University. That geographic reality made Ohio a natural pathway for fugitive slaves.

Freedom-seekers could assimilate into black communities — such as Ripley — that dotted Ohio’s landscape. Or they could be aided by abolitionists, both black and white, who helped them journey north through Ohio and into Canada via the Underground Railroad.

Here’s a sampling of Ohio’s historically significant Underground Railroad sites:

Ripley’s John Parker House and John Rankin House

John Parker, himself a former slave, bought his house (now the museum Scott oversees) and opened a foundry while he continued to help others.

“Parker often traveled back to Kentucky to retrieve slaves and help them across the river, where he would send them along to other Underground Railroad ‘stations’ in Ripley,” Scott says.

One of Parker’s neighbors, John Rankin, was a well-known abolitionist who lived high on a hill. “You could see his house from 30 miles into Kentucky,” Scott says. “His family would hang a lantern in a window to let fugitives know when they could cross the river. Eventually, he helped more than 2,000 slaves to safety.”

Today, the John Rankin House is a National Historic Landmark. Ripley native Betty Campbell, site manager, says the restored house — where Rankin and his 13 children kept the lantern burning — and other Underground Railroad sites are a key part of American history. “They tell the stories of people — men and women, black and white — who helped others achieve freedom.”

The John Rankin House is open April through October, and offers guided tours, exhibits, and a visitors’ center. The John Parker House is open May through October, and includes exhibits and artwork tracing Parker’s life.

Mount Pleasant’s Historic District

Mount Pleasant, an eastern Ohio hamlet between Steubenville and Wheeling, is small — just eight blocks long. The historic district is even more compact, but boasts 40 antebellum houses and another 40 built between 1865 and 1900. “Pretty much the whole village was part of the Underground Railroad,” says Angela Feenerty, president of the historical society in Mount Pleasant. The area was settled by southern Quakers, who brought along slaves who could live freely in the town.

“Most of those hidey-holes you hear about had purposes other than hiding fugitives,” Feenerty says. “This village most definitely had a free black community, and no one from Mount Pleasant was ever sent back.”

On the first Saturday and Sunday in August, a self-guided walking tour lets visitors explore eight historic buildings.

National Underground Railroad Freedom Center, Cincinnati

Cincinnati’s National Underground Railroad Freedom Center is built on the site of one of Ohio’s first black settlements. Says Christopher Miller, senior director of education there, “This area holds a lot of Underground Railroad history, a lot of African American history. Our building sits on what was once called Little Africa, in an area known for slaughterhouses, shipping, and floods. At nighttime there was a great deal of activity as people seeking freedom would cross the river.”

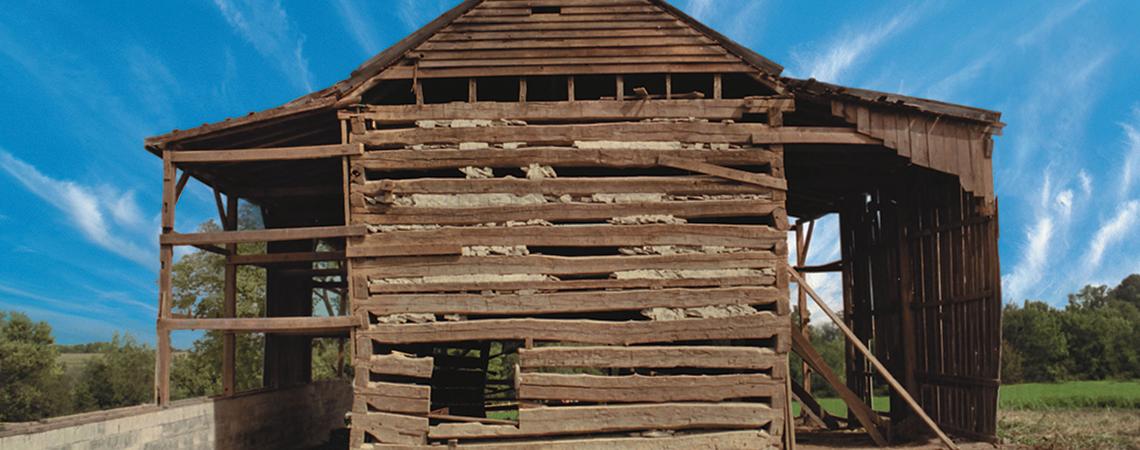

Today, the museum, open year-round, includes exhibits and information from the Underground Railroad all the way to modern-day slavery. One of the center’s most significant artifacts, Miller says, is an authentic slave pen from Kentucky. “It’s important because it helps us get an understanding of the treatment of the African family during slavery.”

Wilberforce and the Afro-American Museum and Cultural Center

Wilberforce was another early black settlement, says Charles Wash, director of the National Afro-American Museum and Cultural Center in the tiny town near Xenia. “Wealthy white Southerners would vacation at the natural springs here with their enslaved female servants, producing mixed-raced children who could not be educated in the South. Many of these children stayed, and Wilberforce University provided educational opportunities.”

Today, the area is home to three historically black educational institutions — Central State University, Payne Theological Seminary, and Wilberforce — along with the museum and its extensive archives. The museum, now in its 32nd year, is open Wednesday through Saturday.

“We’re known for our art and artifacts collection, which is recognized as second to none,” Wash says. Current exhibitions include “Black Power in Comics” and “Art of Soul,” an annual juried show.

Wash, born and raised in Flint, Michigan, moved to Ohio in 2007. “I thought I knew a lot about African American history, but when I moved here and learned about Ohio’s role in the Underground Railroad, it completely blew me away. There is a deep and rich history here in Ohio."