Every May 4, students, faculty, and others on the campus of Kent State University honor the memory of four students killed and nine others injured when the National Guard opened fire during a protest against the Vietnam War on that day in 1970.

That tragedy not only informed a generation, says Alan Canfora, one of the nine who was injured by gunfire that day, “but essentially represented a turning point, in that excessive force was no longer used during the protests against the Vietnam War.” He and his sister, Roseann (better known as “Chic”), who was a witness to the shootings, have devoted much of their lives to making sure that the lessons of May 4, 1970, are not forgotten.

Student Alan Canfora waves a black flag in protest moments before he was shot and injured by National Guard troops. (Photo courtesy of Alan Canfora)

This year marks 50 years since the tragedy, and plans had been in place to commemorate the occasion with dozens of speakers, symposia, and artistic tributes, until the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic canceled the events. Still, the events they had planned are an indication of how much has changed about the way the Kent State community perceives this part of their past.

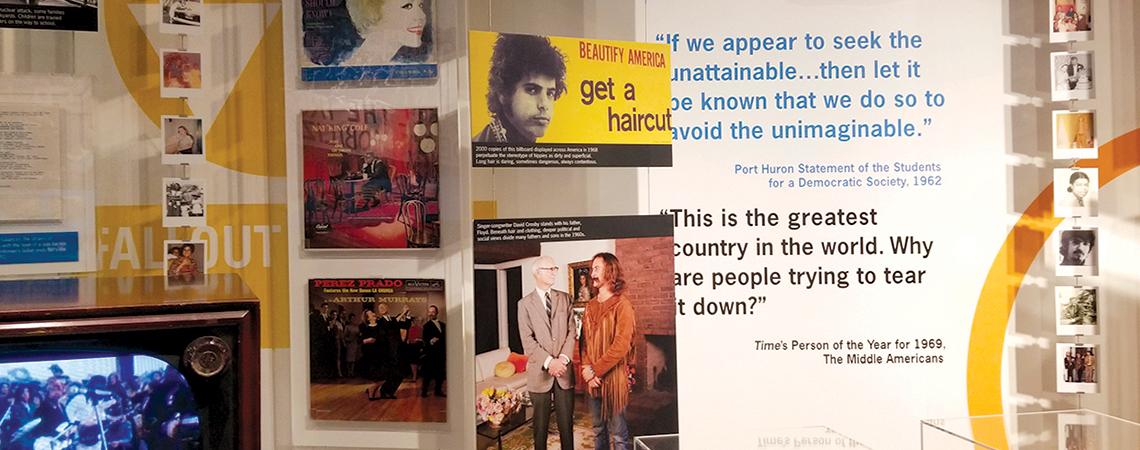

“It took Kent a long time to come to terms with its history,” says Mindy Farmer, director of the May 4 Visitors Center, which first opened in 2014 with an extensive set of exhibits about events there and on other campuses, the 1960s, and Vietnam protests. Freshman orientation at Kent now includes a stop at the center.

Farmer says 2020 represents a sharp contrast from 1975, “when the university decided that five years was long enough to remember the shootings.” After the official commemoration ended that year, a group consisting mostly of students formed the May 4 Task Force, a grassroots organization that would take over the proceedings. That group has been integral in initiating memorials and programs ever since.

In 1977, the university’s decision to construct a gym annex over part of the shooting site further widened the rift. “People came from all over the country to protest,” says Farmer. Students created what became known as Tent City, which stood for two months. It ended only with the forced removal and arrest of almost 200 people — including some of the students injured and families of those who had been killed in 1970. The gym was built, but the struggle lasted for almost two years.

Many of those affected by the events carry it into other parts of their lives. Chic Canfora, for example, is now chief communications officer for Cleveland Public Schools. After the 2018 shootings at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, she went to counsel students there — and while the circumstances of the shootings were vastly different, she says her experience helped them see that others can overcome and manage trauma.

Reconciling the events of the past has been a gradual process for the Kent State community. For example, Karen Cunningham became active in the May 4 Task Force while she was a student at KSU in the 1970s. She eventually returned to Kent as faculty in what is now the School of Peace and Conflict Studies, which was created as a result of the tragedy. She co-teaches a course on May 4 and its aftermath.

Sophomore Ethan Lower’s decision to attend Kent was partially based on family stories about his relative, the late geology professor Glenn Frank, who was instrumental in negotiating with the National Guard immediately after the shootings, helping defuse a volatile situation and preventing further tragedy. Lower is now head of the May 4 Task Force.

In 2019, the university came full circle, once again taking over the commemoration events. Rod Flauhaus, who works in the university president’s office, is the project manager for the 50th anniversary. He also was involved with the task force when he was a student, and worked closely with the group to plan this year’s events.

“While the university allowed the commemorations, they never really embraced them,” he says, until the 1980s, when a series of presidents garnered the support of the trustees and worked to establish educational programs and memorials. Stanchions now stand in the parking lot where the students were slain, for example, and the 17 acres where the events took place is now a National Historic Landmark. “Many of the people who run the university today were students in the 1970s,” Flauhaus says. “The passage of time puts things into a different perspective.”

Sandra Gurvis is the author of 17 books, including a reissue of The Pipe Dreamers, a novel about protests against the war in Vietnam.