In the early 19th century, public city parks were virtually nonexistent. That doesn’t mean, however, that there was no green space in urban areas.

In fact, cemeteries were commonly found within the city limits of even the largest of cities. Most were in churchyards, where bodies were lined up with soldier-like precision to make the most efficient use of available land.

Around that time, Europe embraced a different concept. Instead of a precise grid of graves lined up row by endless, nondescript row and sometimes even stacked upon one another, “garden cemeteries” were designed with trees, ponds, and winding paths. They became places where the living could enjoy a visit, a stroll — even a picnic if they wished.

The trend quickly made it across the pond, and parklike cemeteries began popping up in the eastern U.S. and, before long, in Ohio.

Ohio’s urban garden cemeteries are some of the country’s most distinctive memorial parks, and stunning examples can be found in nearly every population center.

Ohio’s urban garden cemeteries are some of the country’s most distinctive memorial parks, and stunning examples can be found in nearly every population center. Here are three that are particularly outstanding and accessible.

Lake View Cemetery

Garden cemeteries like Cleveland’s Lake View “were made for the living,” says CEO Katharine Goss. Early on, though, only people who owned burial lots could enter Lake View, founded in 1868. A ticket booth stood at the entrance. Now anyone is welcome to visit, and anyone may be interred there.

“Lake View is an all-walks-of-life place,” Goss says.

One of Lake View’s most appealing aspects, Goss says, is the “natural layout … winding roads, big tree canopies. You walk in and you immediately feel your blood pressure go down.”

Lake View’s 285 acres include a large pond, where people may choose to scatter ashes; Daffodil Hill, site of 150,000 daffodils; and walking paths and trails.

The cemetery hosts many events, including concerts, 5Ks, trolley tours, and twilight tours of “Millionaires Row,” whose occupants include Standard Oil founder John D. Rockefeller, the nation’s first billionaire. (Rockefeller’s obelisk is Lake View’s tallest memorial.) Seasonal programs, such as an October Owl Prowl and a December Winter Walk, also are offered.

Lake View memorial adviser Petronella Ragland says the cemetery is welcoming and busy. “People walk their dogs

here, they run, they walk,” Ragland says. (Bicycles, however, aren’t permitted.)

The Haserot Angel, which honors businessman and prominent Clevelander Francis Haserot, appears to be weeping black tears. Weathering is the scientific explanation for the bronze figure’s tears, but visitors nevertheless are startled and moved by the statue.

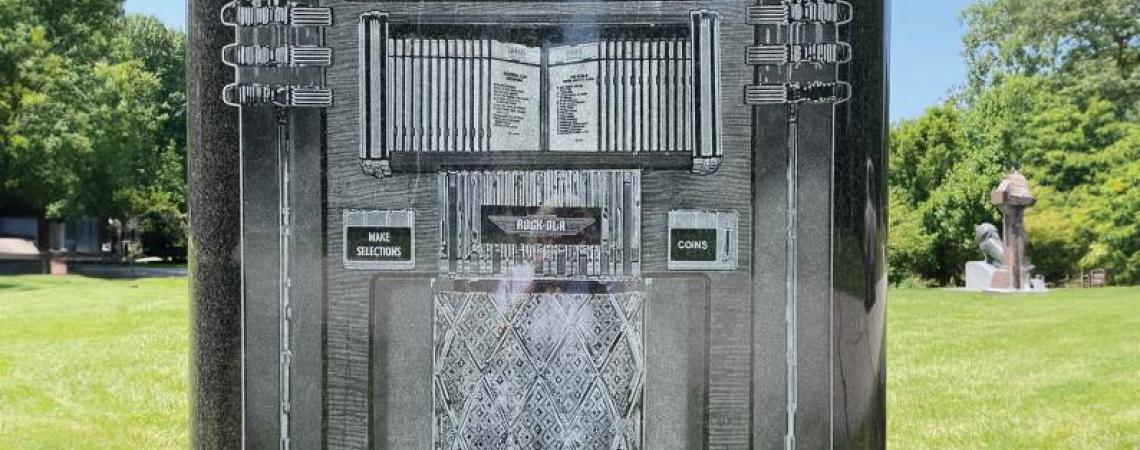

Disc jockey Alan Freed, credited with coining the term “rock and roll,” is memorialized with an intricately carved jukebox. Garret Morgan, inventor of the three-color traffic light and the gas mask, is at Lake View, as is Eliot Ness, the Prohibition officer who brought down Al Capone.

Two steps from Ness is underground comic book artist Harvey Pekar. His grave is blanketed by colorful pens and markers, each poked point-first into the soil.

The display is a spontaneous tribute by the artist’s friends and fans, Goss says. Groundskeepers try to keep leaves and other natural debris from tangling in the pens, but Goss gives Pekar’s widow primary credit for keeping the site tidy.

Raymond Chapman’s memorial also is laden with mementoes. Chapman, who played major league baseball for the then-Cleveland Indians, died when he was hit by a pitch in 1920. He remains the only major league player to be killed during a game.

Chapman’s fans leave many items on his stone. Caps, baseballs, coins, and a Beatles CD were there recently. Cemetery groundskeepers understand fans’ impulse to leave something. They also understand why others take things away.

Visitors don’t swipe mementoes out of malice, Goss

says. They take them for the same reason others left them: because they cherish Chapman’s memory and want a keepsake.

Lake View Cemetery, 12316 Euclid Ave., Cleveland, OH 44106. Open 7:30 a.m.–5:30 p.m. from November through the end of March and 7:30 a.m.–7:30 p.m. from April through the end of October. 216-421-2665, www.lakeviewcemetery.com.

Spring Grove Cemetery and Arboretum

The Cincinnati Horticultural Club chartered Spring Grove’s 220 acres in 1845, and future U.S. Supreme Court Justice Salmon P. Chase, who’s interred at Spring Grove, helped prepare the cemetery’s charter.

For the cemetery’s first 10 years, lot owners tended their own family plots, which made for quite the cluttered look. A new superintendent came on board in 1855, however, and “changed the flavor” of Spring Grove by removing graveside decorations, private plantings, and even fences, says Debbie Brandt, docent liaison at Spring Grove.

He also drained a swampy area, created ponds, and “opened up the vistas,” Brandt says. Visitors in the Victorian Age soon flocked to Spring Grove to see and be seen.

Two of Spring Grove’s more notable spots are a pair of chapels: the Dexter Chapel and Mausoleum, designed to resemble Paris’ La Sainte-Chapelle but never completed despite a staggering $100,000 being spent on it; and the Gothic Norman Chapel, built in 1880 and still the site of funerals, weddings, and even concerts.

Architect Samuel Hannaford, known as “the man who built Cincinnati,” is interred at Spring Grove, along with several names familiar to retail junkies, including Shillitos, McAlpins, and Kroger. Both William Procter and James Gamble are there; Procter’s grave is modest and unassuming, while Gamble’s features a towering obelisk. Brandt theorizes that Procter’s first wife died, and the family lot was created, before the company had risen to obelisk-worthy success.

Also at Spring Grove: mattress manufacturers George Stearns and Seth Foster; yeast maker, Cincinnati mayor, and Reds owner Julius Fleischmann; third baseman Henry Knight “Heinie” Groh, who played from 1912 to 1927, mostly for the Cincinnati Reds and New York Giants; and, maybe, George Turner’s dog.

A story claims that Turner’s dog, Old Man, was buried with his master, thanks to an amiable superintendent. Brandt notes that Ohio law forbids animals from being interred in human cemeteries and no records verify the story. “So I can’t say yes or no,” she says.

Living dogs, normally also forbidden on the grounds, are welcome each Dog Day, held on the fourth Sunday in June. Other events include an annual Lantern Lighting, when participants send paper lanterns, illuminated by tea candles, afloat on a pond, and an annual car show in October. Brandt says 25 docents lead tours — on foot, by golf cart, or on trams — that focus on topics such as history and heritage, the cemetery’s circus connections, or “Movers and Shakers of Cincinnati.” One of the most popular is the Beer Barons Tour in August, featuring well-known brewers such as Christian Moerlein.

Spring Grove Cemetery and Arboretum, 4521 Spring Grove Ave., Cincinnati, OH 45232. Open 8 a.m.– 6 p.m. daily. 513-681-7526, www.springgrove.org.

Green Lawn Cemetery

When Green Lawn Cemetery opened in Columbus in 1849, occupants of older nearby graveyards were relocated there. Adrianne Reese, a Green Lawn family service adviser, says those existing urban burial grounds had been overcrowded and landlocked, so “everybody was moved over here.”

Green Lawn was chartered during a cholera outbreak. First to be interred was cholera victim Leonora Perry, 7, who was buried two days before the cemetery’s grand opening. Another cholera victim, Dr. Benjamin Gard, who contracted the disease while tending patients at the penitentiary, soon followed.

Howard Daniels designed the cemetery to complement the site’s natural beauty. It’s a registered arboretum and is an Ohio Audubon Important Bird Area.

Randy Rogers, Green Lawn Cemetery Association executive director and a tireless cemetery worker, praises Daniels and his foresight.

“We’re unique,” Rogers says. “We still preserve 200-year-old trees that had been preserved by ranchers” who owned the land before Green Lawn existed.

Green Lawn’s 360 acres are home to five Medal of Honor recipients, five governors, and 6,000 veterans.

Writer and cartoonist James Thurber’s marker is flush with the ground, as are those of his family. The only monument in the plot honors a Thurber dog, Muggs, who was immortalized in Thurber’s story, “The Dog That Bit People.” A sculpture of Muggs, looking peevish, is above the engraving, “Nobody knew exactly what was the matter with him. Cave Canem.”

“Little Georgie” is another well-loved grave. George Blount was 5 years old in 1873 when he fell off a banister and hit his head on a stove. His memorial shows him sitting, one leg tucked under the other, a cap in his lap. Visitors once dressed the statue in scarves and hats in cold weather. Now, Green Lawn asks donors to bring such items to the office, to be donated, instead.

For years, Georgie was thought to be interred alone, Rogers says. Recently, however, his father’s military grave was found behind the child’s monument and his mother is in an unmarked grave next to him.

World War I fighter pilot Eddie Rickenbacker is at Green Lawn, as are Ohio Governor James A. Rhodes; Samuel P. Bush, grandfather of President George H. W. Bush; Peter Sells, a Sells Circus co-owner; and Gordon Battelle, founder of Battelle Memorial Institute.

Green Lawn Cemetery, 1000 Greenlawn Ave., Columbus, OH 43223. Open 7 a.m.–7 p.m. in the summer and 7 a.m.–5 p.m. in the winter. 614-444-1123, www.greenlawncemetery.org.