Most folks familiar with Ohio’s geography know that glaciers covered two-thirds of the state, sparing only the southeastern portion from the cold crush of a Pleistocene winter.

The time span and immensity are difficult to grasp: Mile-thick ice spread over the Buckeye State for millennia, gouging and shaping the earth as the ice advanced and retreated. Geologists say that 10,000 to 15,000 years ago, the ice melted and left us our current landscape. That includes the pleasant hummocks piled up where the ice stopped, from Reily in Butler County northeasterly to Salem in Mahoning County.

Look closely and you can see glittering specks among the sand.

The glaciers also left a little prize that they picked up on the slow slog south: gold.

Yes, there is gold in Ohio. You can find it in perhaps most any stream that flows over glaciated Ohio, but the vast majority of the fine flecks of the yellow metal occur where the glaciers advanced their farthest and fell apart — melted — dropping what they had carried along.

Ohio Geological Survey geologist Thomas Nash specializes in glacial geology. Nash says that gold in Ohio is an erratic — that is, it’s not native, necessarily, but transported from elsewhere. There’s no mother lode here; for that El Dorado, you have to look way up north, to Canada.

“Any gold that is found in Ohio today was actually formed in Canada billions of years ago,” Nash says. Gold formed in the bowels of the earth in igneous rocks — those forged by heat. “It was only during the Quaternary Period, considered 2.6 million years ago to present, when gold deposits were transported to Ohio.”

The weight of the massive, hulking ice sheets and the pull of gravity ripped up rocks in Canada, some of which were infused with gold. The gold found in Ohio is typically tiny, flat flakes with rounded edges. They are small and abraded, having broken apart from larger nuggets during the long, grinding trek. Gold flakes as big as a pea have been reported, but those are exquisitely few and far between.

“Gold is a very malleable metal, and the forces and stress that pieces of gold experienced during glacial transport broke the gold down to smaller sizes,” Nash says. “Most gold in Ohio today is found when panning sand in streams and tends to be the same size as the sand grains. It appears as tiny flecks generally less than 2 millimeters.”

Ohio gold has another trait, says Nash: its scarcity. “Gold is very rare in Ohio, and prospectors have found it difficult to strike it rich panning for gold. All of the commercial gold mining expeditions in Ohio’s past were financial failures.”

Gold was discovered in Ohio in the early to mid-19th century, and newspaper accounts of commercial operations making a run at gold extraction corroborate with what geologists know of the patterns of ice flow.

Nash says that two major episodes of glaciation occurred in Ohio, ending in nearly the same places: The most recent flow, called the Wisconsin Episode, almost entirely overlapped an earlier Illinois Episode. That band of exposed Illinois glacial till is where most of the gold has been found, and two places in particular made a fair amount of news through the years, in Clermont and Richland counties.

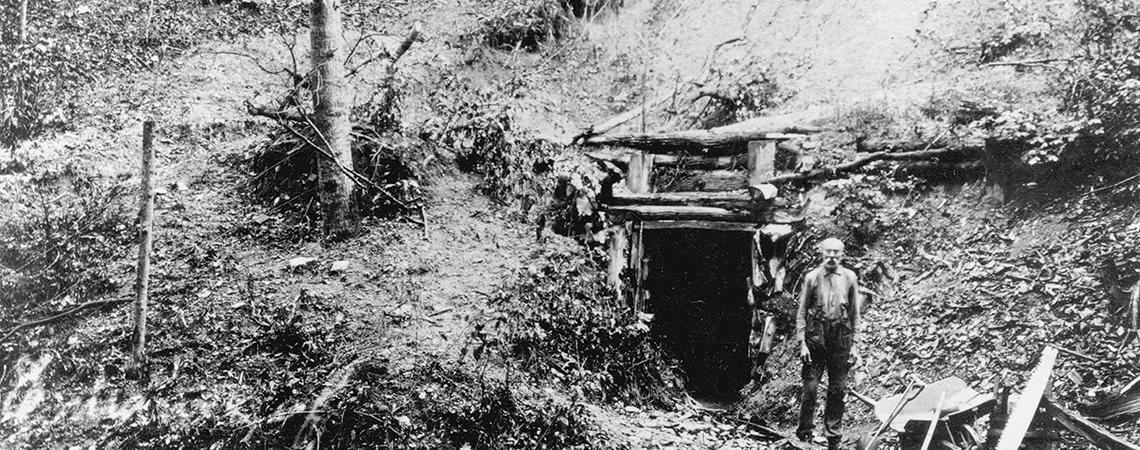

A number of short-lived mines were concentrated close to Batavia in Clermont County and in Bellville in Richland County. These operations relied on the power of moving water to sluice gold from sand and gravel in streams with colorful names such as Stonelick and Brushy creeks, Elk Lick, and Cabin Run in Clermont County. The Elk Lick operation, located on present-day East Fork State Park, spawned the Batavia Gold Mining Company, functional for a short time in 1868, before it was destroyed by a flood.

James Lee, a 49er who returned to Ohio, found gold in Gold Run, also known as Deadmans Run, in 1853. The stream slices through the Illinois till as its waters eventually pour into the Mohican River. The area around Bellville saw intense interest in gold extraction well into the 20th century.

While one can still pan for gold, keep in mind that gold-bearing creeks purl through private property. Don’t trespass. As of this writing, gold sells for $1,876 per ounce. That’s enticing, but don’t expect a great return on hours of shoveling and stooping and swirling a pan. It’s all been done before — and remember Nash’s words: Gold is scarce.

But all that is gold does not glitter, and not all those who wander are lost. Wandering along an Ohio creek bed and turning up stones may reveal other riches — getting to know more about where you live, our natural history, how the past informs the present, and yourself — and that is priceless.