“If [Howard Hyde Russell] could see what’s in his house now, he’d be spinning in his grave,” quips Nina Thomas, the lively and knowledgeable local history manager of the Westerville Public Library.

She’s referring to the ironic fact that the former residence of the founder of the Anti-Saloon League (ASL or the League) is now a fraternity house near the campus of Otterbein University in charming Westerville, Ohio.

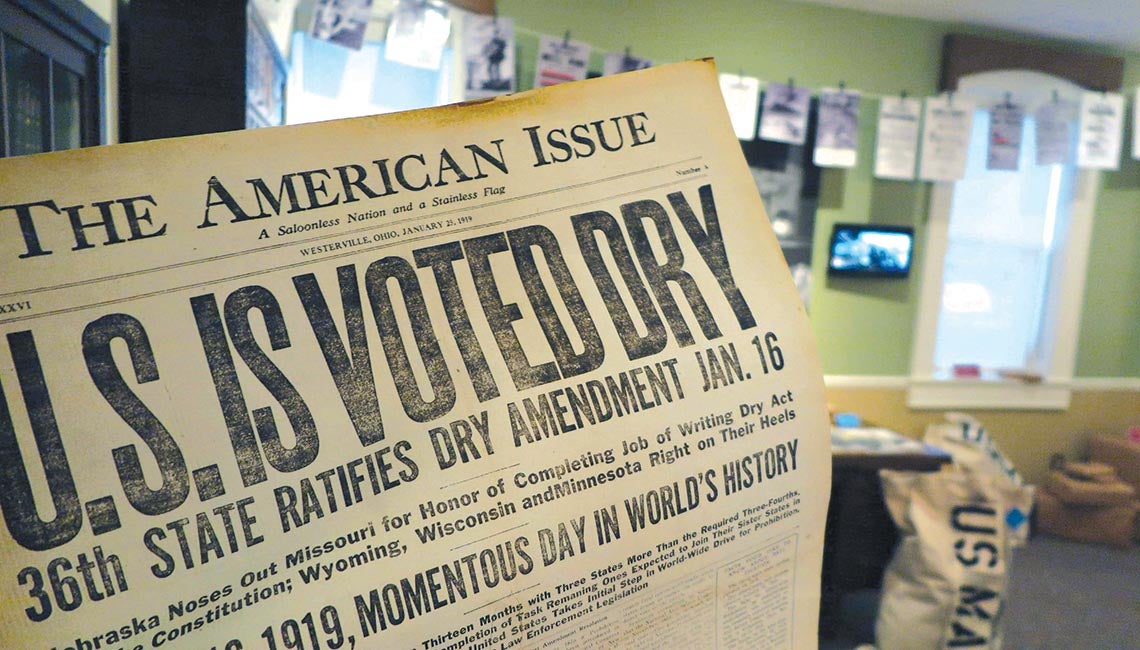

This year marks the centennial of the Volstead Act, which enforced the ban on the “manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors” pursuant to the 18th Amendment. On Jan. 16, 1920, Americans had to give up most of their spirits, wine, and beer, except for whiskey and brandy prescribed for medicinal purposes and sacramental wine used for “religious purposes.”

Many Americans are aware of Prohibition’s unintended negative consequences: It turned ordinary citizens into criminals, created a sharp divide between observers and flouters, and gave rise to criminal syndicates that controlled every aspect of bootlegging, from its manufacture to pricing and distribution. Prohibition’s consequences, however, were more complex than that. The era (1920–1933) brought more freedom for women and led to more integrated entertainment venues and accessibility to jazz; plus, the dry movement led directly to the imposition of federal income taxes.

Ohioans might be surprised to discover the crucial role the Buckeye State played in passing the 18th Amendment and the outsized influence the Ohio-based ASL exercised in making the “dry movement” a national phenomenon. History buffs can head to the Westerville Public Library to view the informative exhibition, “Prohibition: Expectation vs. Reality,” currently on display in the building that was once the League’s headquarters. Although axe-wielding women smashing up saloons made better press, the ASL’s singular focus and application of “pressure politics” at every level of government is regarded as the primary reason the 18th Amendment was ratified.

The dry movement began in the 1820s, before what many historians agree was the apogee of alcohol consumption. According to the exhibit, the average intake in the 1830s was a whopping 7 gallons per person per year (today, it’s about 2.34 gallons). Several factors contributed, including the lack of proper drinking water. The ill effects of so much alcohol consumption spawned a national temperance movement. The initiative, Thomas says, “took a break during the Civil War, but afterwards, many abolitionists joined the temperance movement. It was the new social movement to be part of.”

Howard Hyde Russell was an attorney who attended the seminary at Oberlin College. Russell and other Oberlin temperance reformers formed the Ohio Anti-Saloon League in 1893. The Ohio ASL successfully lobbied the legislature to enact a “local option” allowing towns to vote themselves dry. Russell believed their methods could work on a national level. So Russell and other state delegates met in 1895 and created the American Anti-Saloon League that eventually moved to Westerville.

How did this relatively small group of Ohioans spread the dry movement nationally? The League printed voluminous literature, including newspapers, posters, and other mailings, and stayed constantly on-message. “They were single-issue focused,” Thomas says. “They had no official opinion on women’s suffrage or any other prominent issue of the day” because the League was only concerned with electing politicians who would vote against alcohol.

Another secret weapon was Wayne Wheeler, an Oberlin graduate who worked as an ASL organizer while attending Western Reserve Law School. Wheeler became the League’s de facto head once its goal became a constitutional amendment. A tireless advocate, he was the “dry boss” who controlled politicians and legislators at every level. When the federal government wouldn’t support a national ban because 40% of its revenues came from alcohol taxes, Wheeler played a prominent role in the passage of the 16th Amendment, instituting the federal income tax.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the exhibit is Prohibition’s long-lasting cultural effects: Women began organizing around other political issues, including suffrage; speakeasy owners started hiring African American musicians, thus opening some of the earliest integrated entertainment venues where audiences were first exposed to jazz; and even NASCAR racing can trace its origins to moonshiners, who designed faster cars to outrun the feds.

The League and its leaders have been forgotten. But 100 years ago, they persuaded the nation to embark upon what was originally dubbed “America’s noble experiment.”

“Prohibition: Expectation vs. Reality” on display at the Westerville Public Library, 110 S. State St., Westerville, through the end of 2020.