Travis Wise has been an apprentice lineworker for only about a year, but already he’s experienced the kind of extreme weather that is both the scourge of the lineworker and a source of collective pride.

“In June, we were working 16 hours a day in 90-degree weather, for about a week,” says Wise, 22. “Then winter storm Elliott hit (in December) and we worked a lot of overtime when it was minus 30. We’ve seen the hottest of the hot and the coldest of the cold.”

“Sure, I want to be home,” Wise says. “But there are people out there who don’t have power and if we’re not out there doing this, then who is?”

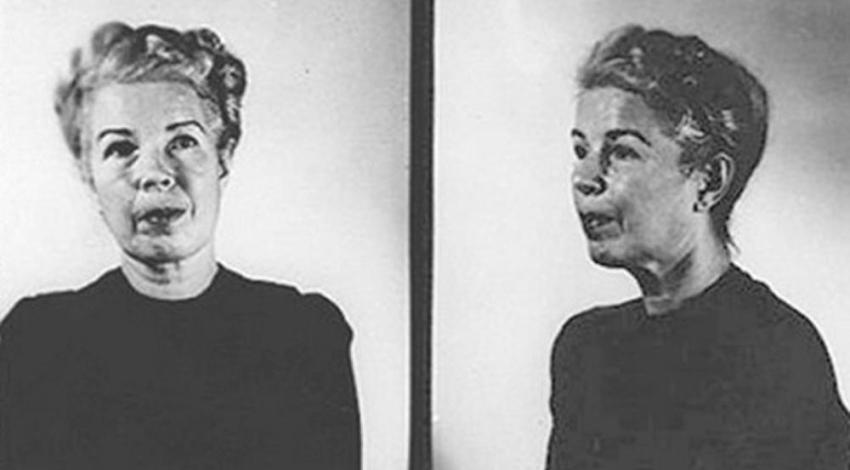

On March 15, 1946, 77 years ago last month, Ohioan Mildred Gillars was arrested by the U.S. Army Counter Intelligence Corps in Berlin, Germany.

Mildred Gillars was born in Maine in 1900 and came of age in Ohio, the stepdaughter of an alcoholic dentist who once practiced in Bellevue. Home life was tumultuous.

She graduated high school in 1917 at Conneaut, near the extreme northeastern corner of the state, and attended Ohio Wesleyan University, where she majored in dramatic arts. Gillars, who went by the nickname “Milly,” took roles in plays and earned a reputation as an excellent orator, eccentric, and a bit of a coquette.

Encountering thousands of bees could be a little disconcerting — maybe downright terrifying — for most of us.

Likewise, Stacey Shaw, safety director and line supervisor at HWEC, has at least 10 beehives on his property near Millersburg, with up to 100,000 bees in each one. “Sometimes, I lie down on the ground and just watch them,” he says. “Each hive has its own personality. Some are really docile, and then you have some that can be more aggressive. But the term ‘worker bee’? They earn that. As soon as daylight comes, they head out strictly for work; they work nonstop until dark and then do it all over again the next morning.”

In April of 2020, we were just beginning to wrap our heads around the notion that the coronavirus pandemic would not simply disappear after the weather turned warm.

If that seems like a modest aspiration, understand that I’ve coveted a rain garden for many years. Designed to temporarily capture and slow the flow of water off your property, rain gardens are a practical and beautiful landscape feature that is becoming popular, especially for those looking to lighten their footprint on the Earth.

Electric cooperatives make substantial investments in the communities we serve, from the power plants that send power across the grid to your local co-op to the poles, wires, transformers, and meters that generally blend into the local landscape. These are all expensive and long-lived physical assets necessary to make your lights come on day in and day out.

Sometime when you feel like getting outdoors and impressing your young kids/grandkids this spring, tell them this story: Say you’re going to visit a king who lives in a castle. Would they like to come along and meet him?

Known variously as crayfish, crawfish, crawdads, mudbugs, or by many other local names, these crustaceans look like mini freshwater lobsters — and taste like it, too. Crawfish boils in the South (especially in Louisiana, where the clawed critters routinely grow much larger than here in Ohio) are highly anticipated party gatherings.

For more than 25 years, children have been bringing colored Easter eggs to the Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Library and Museums (HPLM) in Fremont. Why?

Egg games were popular during the late 1800s, and in Washington, D.C., residents especially enjoyed spending Easter Monday on the grounds of the U.S. Capitol, where they picnicked and watched children rolling eggs — and often themselves — through the grass. After some rambunctious egg rollers damaged the landscaping in 1876, members of Congress promptly protected their turf by passing a law prohibiting people from using the Capitol grounds for a playground. Because it rained in 1877, the law wasn’t enforced until 1878, when police expelled youths carrying colored eggs from Capitol Hill.